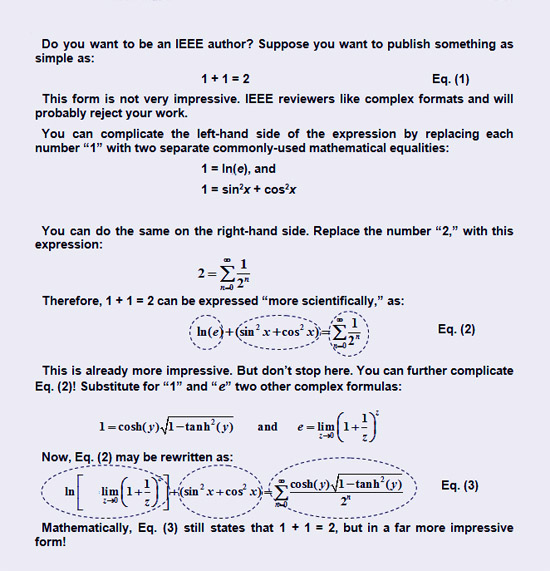

|

My new boss at Fairchild was elated to hear of HP’s decision to terminate me immediately. “You can start working here tomorrow instead of waiting for a month,” he told me. “You can help me interview other engineers for your group.”

Although I was eager to begin, my wife and I decided to take a week off. We drove up to Lake Tahoe and spent a few days planning our next year. After coming home, we began to look for a house to buy. Fairchild’s new plant was already under construction in Palo Alto, so we searched both there and in in Los Altos. Having lived in apartments my entire life, owning a house was a new concept for me. I had heard from my colleagues that homes frequently required repairs—something the apartment managers had always handled for me. However, being an engineer, I was confident I could do repairs myself.

The year 1970 was the busiest of my life. The Early-Bird graduate program at Santa Clara University ran courses from 7 to 9 a.m. Twice a week, I attended morning classes and went directly to work from there. Most of my classmates also held full-time engineering jobs in the Valley. We showed up in the classrooms sleepy-eyed, then rushed to work at the end of classes. It was not an easy schedule to keep, but one advantage of the early start time was the ease of parking on the normally busy campus.

For several months, the employees at our new Fairchild division were scattered among three different temporary locations in Mountain View. The building where I began work was quite spartan compared to HP’s facilities—there was no cafeteria or library. We all looked forward to the completion of our new plant.

My first assignment in this no-frills environment was to design an inexpensive alternative to the hybrid cable TV amplifier produced by HP. I was concerned about the low selling price targeted by our marketing group. Generally, selling price had not an important consideration in my former job. The strength of HP’s Microwave Division lay in its production of unique, low-volume test equipment that had limited or no competition. The cost of the components and manufacturing were of secondary consideration, because their products commanded high selling prices. Even though HP’s cable TV amplifier was a high-volume product, it had no competition. The price could be set relatively high.

In contrast, Fairchild’s expertise lay in high-volume, low-cost products. After seeing the mass-production semiconductor capabilities of the company, I felt confident about meeting the $25 price goal for my project. To keep the cost low, I wanted to find an inexpensive housing for the circuit. The mass-produced TO-3 power transistor package looked suitable for my needs, but it had only two pins available for electrical connections—two less than the four I needed.

Asking around at Fairchild, I learned that Dr. L. of the Semiconductor Division was the company’s packaging expert. I decided to ask his advice and drove to his plant. I located his office but found the area deserted. After a short wait, I saw a man walking toward the office. I stepped into his path and asked, “Are you Dr. L?”

“Yes, what do you want?”

“I’m new at Fairchild and…” was all I could say before he interrupted me.

“Do you have an appointment to see me?”

“No, but all I need is…”

“I don’t talk to anyone without an appointment,” he said, cutting me off again. “See my secretary!” He stepped into his office and slammed the door behind him.

|

Pictures show the top and bottom of an inexpensive standard TO-3 power transistor package. For my amplifier, I wanted two additional leads coming through the metal case, so the package had to be altered. Even though the transistor required a modification, its final cost was only a fraction of the custom-made package used by our competition.

Suddenly, I remembered my HP lab manager’s warning. “Fairchild has a different company culture. You won’t be as happy there as you are here.” He was right! Because most of the key employees of the new Fairchild Microwave Division had come from HP, they still behaved the “HP Way.” We all went out of our way to help one other. However, the first time I stepped out of our division’s boundaries, I discovered that kind of cooperation did not exist at Fairchild. Eventually, on my own, I found a vendor who agreed to modify the standard package at a reasonable price.

The next step was to write a CAD program to design high-frequency circuits. I added a user interface to our previously developed routine stored in Stanford’s computer and entered it into the General Electric (GE) Timeshare System. One of the added features of the GE system was a large database to store the measured parameters of Fairchild’s microwave transistors. Marketing agreed to have the program available to designers to promote Fairchild’s transistors. To emphasize how fast the program was, I decided to name it SPEEDY.

In a short time, SPEEDY became popular worldwide. Circuit designers no longer had to rely on datasheets or characterize their microwave transistors, as long as they used Fairchild’s devices. The company recognized the competitive advantage created by the program, and I received an additional stock option.

Finding experienced microwave circuit designers was very difficult. We could no longer recruit engineers from HP. Our management decided to look for bright young engineers and teach them the computer-aided techniques. Two of the new hires came with interesting backgrounds.

One of them, a recent young emigrant from Romania, had no U.S. experience, but he sounded promising during the interview. We offered him a job and expected him to grab the opportunity immediately. To my surprise, he waited several weeks before accepting the offer. It took months before I finally learned why he had hesitated.

During a company dinner to celebrate the completion of our new building, he approached me carrying two glasses of wine. “Les, there is something I must confess to you,” he began after toasting me. “When you offered me a job, I knew you were a Hungarian. You knew I was from Romania. I thought you wanted to hire me only so you could give me lots of trouble.”

His revelation at first surprised me. Then I realized how much ethnic hatred existed among the various Eastern European countries whose borders had changed frequently during and after the two World Wars. Fortunately, I had lived far away from those troublesome border zones. Other than disliking the Russians for imposing their political system on us, I did not have any reason to dislike other nationalities. I reassured Peter that I held no such ill feelings. He and I remain good friends to this day.

Professor Chan, Chairman of Santa Clara University’s EE department, recommended the other new employee. “One of my Ph.D. candidates is a giant,” he told me. “He is head and shoulders above all of my other students. Although he has no practical design experience, I’m sure he’ll learn fast. His name is Chi Hsieh. Talk with him.”

I called the student and arranged an interview for the next day. At the agreed time, our receptionist paged me. “Mr. Hsieh is here to see you.”

Eager to see the “giant,” I rushed to the entrance. The lobby was empty except for a young, small-framed boy sitting on one of the chairs. I assumed he was the son of an employee. “Where is Mr. Hsieh?” I asked the receptionist.

“Right there,” she replied, pointing to the young man.

Based on the boyish appearance of the applicant, I seriously questioned Professor Chan’s judgment. During the interview, however, my doubts quickly faded. Although he lacked knowledge about the latest microwave technology, the student had logical reasoning skills and a strong grasp of the basics. We hired him, and it did not take long to realize why his professor thought so highly of him. What had taken me months to learn at HP, Chi picked up in mere weeks at Fairchild. He quickly became one of our most valuable design engineers.

After happily moving into our new Palo Alto facility, Fairchild faced some unpleasant news. About a third of the new building extended into Los Altos Hills. That city, primarily a bedroom community, had strict building codes that Fairchild had violated.

Los Altos Hills did not allow manufacturing activities, and our semiconductor production facility happened to be on their side of the city line. Petitioning the city and offering to pay a fine to allow the operation to remain there did not help. A costly and time-consuming reshuffle of the work areas moved manufacturing to the Palo Alto side.

The next inspection found that the building exceeded the Los Altos Hills’ height limitation by 18 inches. This was a more difficult problem to overcome, because we did not want to shave off the roof. Finally, following the recommendation of an outside consultant, the company ordered a large amount of soil to raise the ground level around the building on the Los Altos Hills side. Fortunately, our main entrance faced Palo Alto, so the front door remained unblocked.

About the same time as this monumental “landscaping” project was going on, one of my colleagues asked me to coach kids’ soccer. The team was part of a California-based organization called AYSO. [*American Youth Soccer Organization, a group that advocated sportsmanship above all, specified that every child must play at least one half of each game, regardless of his or her skill level. Established in Los Angeles in 1964 with nine teams, today the organization has over 50,000 teams throughout the United States.] I agreed, remembering how much I had enjoyed playing soccer. I thought it would be fun to coach and also welcomed the opportunity to get more exercise. Soccer was fairly new to the American sports scene, and his team of six- to seven-year-old boys and girls, the Panthers, had absolutely no idea how to play. In our first game, they all crowded around the ball, trying to kick it regardless of what direction the ball should go. Within a few months they learned the basics, and the games became more enjoyable for all. I stayed on and coached for several years.

As if the weekends weren’t busy enough with soccer games, I was part of a group of other local IEEE chapter officers who decided to organize Saturday design seminars for Bay Area engineers. We managed to secure the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC) auditorium for the one-day courses at no cost, except for the lunch provided by their cafeteria. We charged $10 to IEEE members and $20 to non-members and planned to set up scholarships from the revenues. The first course, entitled Computer-Aided Circuit Design, was an overwhelming success. Over 300 people attended the inexpensive continuing education program. We immediately made plans for follow-up courses.

Serving lunch to such a large number of people took far more time than we had scheduled. The cafeteria manager could not find any way to speed up the process. Later, when I expressed my frustration about the slow service to my mother-in-law, Doris Bogart, she offered a surprising idea.

“Let my service league ladies (CAC) serve lunch to your group,” she suggested. “We’ll buy sandwiches and hand them out quickly. Your engineers can sit at the outside tables and eat in a nice peaceful environment. Pay us the same as you paid SLAC.”

I liked the idea and agreed to try it at the next seminar, knowing that any profit they made would go toward a good cause. Her service league of volunteers had been formed several years previously to help the families of jailed inmates. The other IEEE officers also liked the idea.

My mother-in-law showed up with a large number of ladies on the day of the next course. They handed out the lunch and the refreshments smoothly. The sandwiches were so large that most people took only a half. Everyone was satisfied, and there were even leftovers. Mrs. Bogart’s group became the food provider for years to come. In fact, when other IEEE chapters heard about the success of our courses and formed their own, they also invited her group to serve their lunches. Thousands of engineers attended our chapter’s course series during the following years. We set up college scholarships from the revenues.

The real estate agent we had contacted earlier called us one evening. “Looks like I’ve found the perfect house for you,” she said. “Let me show it to you.”

A few days later, she drove us to the three-bedroom home, located on a third-acre parcel in a Los Altos cul-de-sac. The house was in good condition with an appealing front yard. The property was listed at $33,000. After my wife saw the blossoming fruit trees and flowers in the garden, she grabbed my hand. “I love this place. Let’s buy it.”

The idea of becoming a homeowner was still somewhat scary. “Let’s wait another year,” I replied. “I’m so busy at Fairchild and settling into a big house will take even more work.”

“A year is a long time. We should bring our child home to a house instead of an apartment.”

It took me a few seconds to absorb her last statement. “Are you pregnant?”

“Yes! We’ll have our baby in August.”

I hugged her with excitement. “Of course we’ll buy this house!” We offered $30,000 to the seller and settled at $31,000.

Moving into the house required buying additional furniture and appliances as well as maintenance equipment for the garden. A lawn mower was one machine I had never used before. I had seen other people using those noisy beasts, and I was eager to try one myself. During the first weekend of our occupancy, following the instructions I received from the Sears salesman, I began to mow our lawn.

After finishing the front yard, I went to the back of the house. About halfway through that lawn, the engine began to sound muffled. When I removed the bag, I noticed that the chute was clogged up. I reached down with my left hand to clear the opening.

Something hit the tip of my middle finger. Pulling it back, I noticed it was bleeding. Fortunately, the sharp rotating blade had only cut a small gash that healed in a few days. After the damage was done, I read the instructions: “Never place anything into the chute while the motor is running!”

Once we had a house, the next step was to find a pet. A neighbor’s dog had a litter, and we adopted one of their adorable male shepherd-husky puppies. For some reason I gave him the name Tarzan, and he quickly became the center of our affection.

|

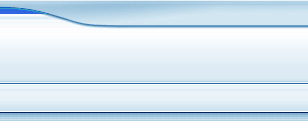

Left: Our first house in Los Altos. Its value has appreciated by about a factor of 50 during the past 40 years. |

Five years had passed since I had last seen my mother. Rather than going back to Budapest, Joyce and I decided to see if the Hungarian government would allow Mother to visit us for the arrival of our first child. Legal travel to a Western country from Hungary was not routine in those days. The Communist government carefully guarded against the possibility that someone might not return to the “workers’ paradise.” My only hope was that because my 60-year-old mother was a pensioner and had an apartment, the officials might be relieved if she did not come back.

We filed the necessary paperwork from both ends to request an exit permit and a U.S. visa for her. A few months later, her trip was approved. Our baby was due in late August, so we planned Mother’s visit to coincide with the occasion.

The Los Altos Town Crier had a contest for a “Good Guy” award, and I nominated my wife for it. To justify her case, I stated that instead of purchasing new furniture for our house, she had agreed to spend the money to bring my mother from Hungary to see her grandchild. The editors liked my reason and selected Joyce as the winner. We received a certificate for three people to dine in one of the Los Altos restaurants.

Joyce and I picked up Mother at the San Francisco airport after her long journey. Although she looked tired, she was happy to see us and congratulated me on having such a pretty wife. In the airport garage, I proudly had her sit in our car, and we proceeded to drive to our house.

After arriving home, I parked the car in front of our house. “This is where we live,” I announced to my mother, expecting a favorable response.

Until that point, she had been impressed with everything: my wife, our car, and my ability to maneuver in busy traffic. After looking around at our street, however, she became subdued. “But there are no sidewalks on this street,” she said quietly.

At first, her comment surprised me. Then I remembered how the city people in Hungary looked down on those who lived in the country. They felt that civilization ended where the sidewalks ended. It took quite some time for my mother to accept that her college-graduate son lived in a country-like environment.

|

| The Goose-Tender Matyi statue, made by the famous |

Inside the house, Mother unpacked her luggage and proudly gave us the presents she had brought with her. First, she placed several Hungarian Herend porcelain figurines on the carpeted floor of the living room. Then she reached into her carry-on bag and pulled out a large bowl. When she removed the lid of the bowl, Joyce and I saw a huge cooked goose liver sitting in the middle of hardened goose fat. She had smuggled the liver through customs! When the aroma reached me, I excitedly jumped over the figurines for a closer look. Unfortunately I did not raise my feet high enough and kicked off the head of my favorite figurine, called Ludas Matyi (Goose-Tender Matty). Mother was horrified and began to cry. Throughout her long trip, she had carefully hand-carried and guarded the precious gift, and I had carelessly broken it.

My clumsy jump dampened her cheerful mood. She only stopped crying when I assured her that I knew about a special store that handled china restoration. They could reattach the head. She fully recovered when I asked to eat some of the goose liver. With a beaming face she served the liver and also spread the goose fat on bread. Now, I know how unhealthy that meal was, but in 1971, I was not concerned about a proper diet.

Joyce’s due date approached and passed, but our baby did not show any desire to appear. We had a suitcase packed, and I was on standby to rush her to the hospital at a moment’s notice. Nearly a month later, she called me at work one afternoon, “The time is here!”

I arrived home within ten minutes. After passing on the news to Mother, I led Joyce to the car, tossed the suitcase into the back seat, and rushed to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Gatos. A nurse led us into a small room and notified Joyce’s obstetrician, Dr. Trueblood. He soon showed up in a grumpy mood because he had had to leave his daughter’s birthday party.

“You still have a way to go,” he announced after his examination. He instructed the nurse to notify him at the right time and went back to his daughter’s party. Joyce and I were left in the room to practice the Lamaze technique. [*A breathing technique to make childbirth easier.] Our baby, however, was not in a hurry to join us.

Dr. Trueblood appeared again. This time he was eager to speed up the process. “I’ll give you a shot that will help,” he told my wife.

I went out to call my in-laws and my mother with the latest news. When I returned to the room, it was empty. I ran out into the hall.

“The shot sped up the process,” a nurse told me. “She is delivering right now.” I raced to the delivery room.

Early on the morning of September 24, 1971, our son George was born. The staff allowed me to hold him in my hands, close to my heart. He had blue eyes, long dark hair, and a loud cry. The noise he made sounded better than any music I’d ever heard. I was the happiest man in the world. I had become a father!

When I returned home from the hospital, my mother was eagerly waiting for me at the door. “Hello Grandma,” I greeted her.

“Is it a boy?” she asked nervously.

“Yes.”

Her face suddenly relaxed. She ran over and hugged me. “I’m so happy.” Only then did she ask me how my wife and son were doing.

Like most traditional Hungarians, it was important to her that the first child was a boy to carry on the family name and responsibilities. Later she told me that she would love a granddaughter just as much. However, she was happier for having a grandson.

After Joyce came home from the hospital, I quickly learned that babies do not have the same sleeping habits as adults. Waking up in the middle of the night to help with George became part of my life. What amazed me was that I did it without any resentment. I enjoyed becoming a parent and carried out my duties faithfully. Even changing messy diapers did not bother me. I will always feel sorry for people who go through life missing the experience of holding and comforting their own helpless little child.

|

Left: The photo in the Los Altos newspaper article, dated August 18, 1971, shows my nine-months- pregnant wife |

My mother still lived in the same apartment we had had before I escaped from Hungary. It lacked central heating, hot water, and any place to take a bath or to shower. The building had no elevator, and climbing the stairs to the third floor became harder for her as the years passed. Her efforts to upgrade to a better apartment had been fruitless. I decided to visit her in the summer of 1973 to see if I could help her find a more comfortable place for her later years. Joyce had never been to Europe, so she was eager to come along. George was nearly two years old, and we decided to take him with us. The airlines provided bassinets next to the bulkheads of the planes, making the long flight quite comfortable for small children.

Most of the tenants in the apartment building still remembered me. They all wanted to meet my American wife and child. The fact that neither of them understood Hungarian made the meetings somewhat awkward, but I did my best to translate their conversations. Mother, of course, was always present to show off her son’s family.

We met Pista’s family, who still shared an apartment with his wife’s parents. Joyce was amazed to see that four adults and three children shared one bathroom. I explained to her that it was not unusual. Although World War II had ended nearly 30 years before, obtaining an apartment in Budapest was still very difficult. The socialist government had placed higher priority on developing heavy industry. Rebuilding the war-torn city without foreign investment was going slowly.

|

Left: George is taking a bath at Józsi bácsi’s apartment, using the same tub in which I had my first bath when I was three years old. |

Pista helped me find a couple who was interested in trading their small one-bedroom apartment located in the outskirts of Budapest for Mother’s larger place that was centrally located. The other apartment was on the sixth floor of a panel-house, [*Many of the newly constructed government-owned buildings were built with large prefabricated steel-reinforced cement panels.] but the building had central heating and an elevator. The apartment had a small bathroom equipped with a gas water heater. A bus stop located only a block away offered convenient transportation to the inner parts of the city.

The couple agreed to the trade—if we would provide an additional one-time payment “under the table.” We used up most of our traveler’s checks to satisfy their demand. Every apartment building in Budapest was owned by the government, so the trade still had to be approved by the housing bureau. Paying a small bribe to the official helped to speed up the process. The moves were scheduled to take place about a month later. Pista and his friends promised to help Mother when the time came.

Although Mother was eager to cook for us every day, we all went to a restaurant on the first Sunday. Prior to leaving California, we heard that Hungarian restaurants did not have high chairs, so we took a special harness with us to keep George on a chair.

When we tried using the harness for the first time in a restaurant, George did not like it and made his displeasure known. All the other customers stared at us. They also made unflattering comments about “tying a poor defenseless child to his chair.” Finally, the waiter came and asked us to untie our son or leave. Not wanting to be thrown out, I placed George on my lap and we ate our dinner together. After that day, we always ate at home.

Mother told me that my father had passed away earlier that year. She wanted to show me his gravesite in a cemetery on the Buda side. I was not really interested in going. Even though he was my biological father, he was never a dad to me. However, to please her, I agreed to go. At his gravesite, I said a prayer for his soul and forgave him for not being a real father to me.

|

Left: My sister, Eva, visited Budapest at the same time. Mother and Joyce are holding a new toy for George. |

Our two-week stay went by quickly, and we returned to the United States. After settling back in our own comfortable house, I thanked God for leading me to California. I had enjoyed visiting Budapest, but I had become used to living in this country. This was now my home.

During the spring of 1972, the semiconductor industry experienced one of its cyclical slowdowns. Although our division was growing rapidly, we received an order from Fairchild corporate to lay off 10 percent of our staff. Our division manager refused to comply. He called a staff meeting in his office to discuss how we would pass through the difficult times. During the meeting, his secretary stuck her head into the room. “Excuse me, Dr. Attala, but Dr. Hogan would like to see you,” she said in an apologetic tone.

“Continue our discussion. I’ll be back shortly,” John told us as he walked out of the office.

Suspecting nothing, we kept on with our planning. An hour passed, but our leader had not returned. Finally, his secretary showed up. “Please go back to your workplaces. Dr. Attala was fired,” she announced in a tearful voice. “Dr. Van Poppelen will be our new division head.”

The news shocked all of us. The Microwave Division had already developed a unique product line. Our Gallium Arsenide Field Effect Transistors (GaAs FET) and low-noise microwave transistors had no competition, and the defense industry had already booked our entire production capability. We could not understand why Fairchild’s management did not see the bright future of our division. They had made a drastic cost-cutting decision for the entire corporation, ignoring how much our division was contributing to the company.

At that point, I had had enough of Fairchild and begin to look for another company that cared more about its employees. A friend who owned stock in a medium-sized firm located in San Carlos recommended that I talk with the people there. “Farinon is like a mini-HP,” he told me. “I know several people who work there, and they’re all very happy.”

The physical appearance of Farinon’s plant was not very impressive; it looked like a large warehouse. I had become spoiled by the sparkling new Fairchild facility in Palo Alto. But the Farinon employees I met during my first interview impressed me so much that I quickly decided to work there. Their open and friendly attitudes, combined with their enthusiasm about the company, convinced me that I would be happy.

A few days later, I went back for a second interview to see Ed Nolan, Farinon’s VP of Engineering. Just like the engineers I had talked with earlier, he was open-minded and personable. He wanted to know more about my computer-aided design experience. I told him about the design program I wrote for my Master’s thesis on the small IBM computer at the University of Santa Clara. It was more advanced than SPEEDY, because it also included circuit optimization. [*An iterative technique to find the best values of circuit components for optimum performance.] “Our engineers are still doing manual calculations instead of using computers. You could help them to become more efficient designers,” he said, and made me an attractive job offer.

I decided to give up my stock option and resigned from Fairchild after being there for two years. They did not walk me out the door like HP had. Two weeks later, after passing my responsibilities on to another engineer, I began to work at Farinon. Three others from Fairchild also decided to follow me. One of them was Chi Hsieh, the “Giant,” who by that time had become an expert in computer-aided circuit design. The other engineer, Bob Griffith, played a vital role in setting up Farinon’s microcircuit facility. The third person helped to train newly hired production assemblers in the microcircuit lab.

My first assignment at Farinon was to rewrite my thesis program to operate on a commercial timeshare system called NCSS that used an IBM 370 computer. My company paid for the computer time required for the conversion. Based on an agreement with Ed Nolan, I retained ownership of the software and all Farinon employees could use the program without paying royalties.

I transferred the program from the university into NCSS’s computer via punched cards. [*Stiff paper cards that contained digital information by the presence or absence of punched holes in predefined positions. Nowadays, the same information is stored in digital format.] It required quite an effort from me to make the conversion from standard FORTRAN to the proprietary language of NCSS. When the program finally ran on the timeshare system, I asked the engineers to propose a suitable name or acronym to describe its function. One of them came up with Computerized Optimization of Microwave Passive and Active ComponenTs (COMPACT). I rewarded him with a dinner in a Hungarian restaurant and began to train my colleagues on the computerized approach. Most of them were eager to learn, although a few still preferred to use the hand-held calculators.

|

Before video terminals became available, I used COMPACT with an "intelligent printer," that was connected through |

More Information |

|

This photo shows another company's |

A few weeks later a salesman from a competing timeshare company, United Computing Services (UCS), stopped by to demonstrate their microwave circuit design program. After hearing that we had been using a program that could even optimize a circuit, he asked if he could come back with their technical experts to see how it worked. I agreed, and he showed up next day with two other men. They were impressed to see how quickly COMPACT found the best component values. My program was user-friendly; it used intuitive abbreviated names for the components, such as RES for a resistor and CAP for a capacitor. Their software used numerical codes that required memorization by the users. I had also written a user manual for COMPACT that included typical examples for various types of microwave designs.

“Why don’t you put this program on our system and collect royalties for its usage?” asked the salesman, when he heard that I owned the program. “We’ll do the conversion to our system at our expense and reprint the manual for our users,” he offered.

That idea had never occurred to me, but I liked it. “Let me ask my boss,” I replied. “Come back tomorrow.”

I knew that the founder of our company, Bill Farinon, had always advocated entrepreneurship. Whenever anyone approached him with an idea of leaving Farinon to start a new business, he was willing to help finance it—as long as the other person put up a significant part of his own money. However, I did not plan to leave my job, so I knew my case would be different.

My manager did not object to the idea but wanted to talk it over with Ed Nolan. Later that day, they called me in. “COMPACT is your property and you can do whatever you want with it on your own time,” said Ed. “I don’t like the idea that our competitors might also use it, but at least they have to pay for it and we don’t. Go ahead and try it!”

Encouraged by the enthusiasm of the UCS salesman and blessed with the green light from my bosses, in late 1972, I formed the company known as Compact Engineering. In a few weeks, COMPACT was running on UCS. After testing it during a weekend, I gave them the go-ahead signal. A month later, I received a royalty check for over $1,000, which was more than my monthly salary at HP had been. The long hours spent writing and converting COMPACT were beginning to pay off in a big way.

During the spring of 1975, my father-in-law called with good news. We were going to Japan! Mitsubishi had been building huge oil tankers for Standard Oil. Whenever a new ship was ready, an entire family of Standard Oil executives was invited to the launching ceremonies. That year, my father-in-law, Nelson Bogart, was selected for that honor. His wife was to cut the rope that symbolically tied the ship to the pier. The extended Bogart family included 20 people: parents, children, siblings, and even cousins. Mitsubishi paid for all the expenses of the two-week trip.

The trip was marvelous. We received royal treatment all the way. After a first-class flight from San Francisco to Tokyo, our group was whisked through Japanese customs and immigration. Mr. Yoshida, the head of our host committee from Mitsubishi, welcomed us at the airport. He handed everyone in the group a detailed schedule for our visit. A small caravan of limousines took us to a five-star hotel in Tokyo where we spent the first three days.

Our hotel was located next to the American Embassy. From the window of our room on the 25th floor, we could look down and see groups of people demonstrating against the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Police carrying large shields protected the building and hauled away some of the protesters. I felt like I was watching a silent movie, because we could not open the window to hear the noise.

Each day had been meticulously planned for us from morning through the late evening. In addition to visiting museums and historical sites, attending sporting events, and shopping, Mrs. Bogart had an additional task on her schedule. She had to practice the cutting of the rope. An ancient superstition stated that the ship would only be protected from evil spirits if the rope were cut in a single chop. Every day, Mr. Yoshida and a white-gloved assistant called on her. They carried a chopping block, several pieces of a two-inch diameter rope, and the razor-sharp hatchet.

I witnessed her first practice session, where it took her five or six strikes to cut through the rope. Although, like most Japanese men, Mr. Yoshida did his best to hide his emotions, we could see that he was quite concerned. By the third day, however, she did succeed once with the first blow.

We found real bargains while shopping. The exchange rate of the U.S. dollar was 400 Yen. I bought a Nikon camera with an F1.2 lens for about half of what it was selling for in California. Inexpensive silk kimonos and genuine pearl and coral jewelry were extremely popular with the ladies in our group.

Another memorable experience was the integrity of the shopkeepers. When I bought the camera, I gave the salesman who stood on the other side of the counter a 100,000 Yen bill. He courteously bowed while accepting the money from me. Then he took several smaller bills from the cash register and handed me the change on a small tray. After counting the amount, I placed the money in my pocket.

When we left the store, someone in our group who had previously spent time in Japan told me that I should not have checked the amount the salesman gave me. “To him, it was an indication that you didn’t trust him,” he explained. “Japanese people are very honest. You never have to count the money they return.”

I followed his recommendation, although at the beginning, I still checked the amount once I was outside the store. It was always correct, so eventually I stopped checking.

On the evening of the third day, we flew to Nagasaki, the city where the second atomic bomb had been dropped during World War II. Other than a large memorial, there was little to remind us of the once horribly devastated area. The busy modern city had been completely rebuilt. The next day we visited the hill overlooking the harbor where the story of Madame Butterfly was set. From the hill, we could see the new supertanker being prepared for its launching ceremony.

Instead of the Western-style hotel where we had stayed in Tokyo, our Nagasaki residence was traditional Japanese. We enjoyed the new quarters that included Japanese baths with steaming hot water. My only negative experience took place during the first night. After drinking lots of beer and sake at dinner, I had to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. I forgot that the door openings were only about five foot eight inches high. As I walked in the darkness, I banged my head on the upper part of the door frame and developed a large bump.

The rope-cutting practice sessions continued. By the fourth day, Mrs. Bogart managed to cut through with a single hit most of the time—but not always. There was only one more day left to practice until the launch.

Finally, the highlight of our trip arrived. On the morning of the sixth day, our hosts took us to tour the huge oil tanker. The top deck exceeded the length of two football fields. The sophisticated control system assured a balanced configuration of the cargo. Two monstrous diesel engines provided the power to carry 40 million gallons of oil at the speed of 10 knots.

|

Left: Watching the entertainment in a Japanese geisha house. |

Although she complained about a sore wrist, my mother-in-law agreed to Mr. Yoshida’s request for a final rehearsal. The results were not promising; she failed twice to completely severe the rope with the first strike. Everyone was tense during lunch and avoided talking about the rope cutting.

In the early afternoon, the sharply dressed crew stood at the side of the top deck. Our group, along with the Japanese dignitaries, was seated under a large canopy on the shore. A band played first, followed by speeches from Mitsubishi's executives and the captain of the ship. Language interpreters were seated behind us to translate the Japanese speeches. Then the band played again, and Mr. Yoshida led my mother-in-law to the designated place where the rope was stretched. He handed her the hatchet and stepped aside. I was close enough to see that her hand was shaking. The music stopped, followed by silence as Mrs. Bogart raised the hatchet. She lowered the sharp instrument until it touched the rope, establishing her aim. Then, with one self-assured swift strike, she sliced through the rope.

The crowd erupted with joy; everyone clapped and yelled. She looked relieved as the giant ship slowly began to slide into the water. At the banquet that followed, the president of Mitsubishi expressed his thanks by presenting her with a beautiful pearl necklace.

The rest of our traveling group was to continue the tour, but Joyce and I were flying back home at the end of the first week. On the way to the Nagasaki airport, we had a great idea: we could downgrade our first-class tickets to tourist class and use the refund for a trip to Hawaii sometime later. The airline complied with our request and placed us back into the coach section of the plane. It was a very different experience than our first-class trip over, but we told ourselves that tolerating the cramped quarters would be worth it for the extra vacation later. However, our scheme backfired on us. Instead of sending a check to us for the difference, the airline issued the refund to Standard Oil, because the tickets were paid by a corporate credit card!

Shortly after COMPACT became available at UCS, other timeshare companies also wanted the program on their computers. Fortunately, my agreement with UCS was not exclusive. By early 1975, COMPACT was running on five international timeshare services worldwide, without any competition. Although the University of California at Berkeley had also developed a large circuit simulator called SPICE, it did not have the input and output capabilities needed for microwave circuit design. Some of the larger companies, like HP and Texas Instruments, had their own in-house programs. Most of the firms, however, focused on hardware product development and used COMPACT. By a stroke of luck, I found myself with a global monopoly of the commercial computerized microwave circuit design.

The intensity of the Cold War was increasing, and the demand for new telecommunication, spyware, and Electronic Warfare (EW) products was high. The defense industry was busy providing for the needs of the Defense Department. Money was no object. The government was willing to pay the price for performance.

My royalties were increasing but so was the demand for product training and support. My wife already helped to answer telephone calls, but most users wanted immediate help. Farinon’s management was extremely understanding and allowed me to take a limited number of COMPACT-related phone calls at work—as long as I continued to fulfill my job requirements. As a result, I spent long days at the plant. At home, I worked on program enhancements and looked for solutions to the customers’ problems. I was not sleeping much.

Early one morning, while I was still at home, an East Coast user named Bob phoned and asked for help with his circuit. During our conversation, he had to step away for some reason, but he promised to call back soon. Ten minutes later, the phone rang. When I picked up the receiver, I could tell by the hissing noise that it was a long distance call. [*This was decades before Caller ID became available.]

“Hi Bob,” I said, assuming it was my customer again.

“How…how did you know that it was I?”

“I have ESP,” I answered, trying to be funny.

“That’s incredible…” the man mumbled. “I must meet you one day in person.”

As it turned out, the second caller’s name was also Bob, but he was not the same man who had phoned earlier. Only when we met at an IEEE conference years later did I tell him the truth. Until then, he really believed that I had a special gift.

A caller from a Canadian defense organization named Communications Research Centre (CRC) told me that their engineers wanted to use COMPACT. Their security requirements, however, would not allow them to pass circuit information through outside telephone lines. “Would you sell the program, so we could install it on our secure in-house computer?” he asked me.

That question had never come up before, but I did not want to turn business away. “Yes,” I replied.

“How much does it cost?”

I had no idea what the program would sell for. “Fifteen hundred U.S. dollars,” I said meekly, ready to negotiate.

“I’ll send you a purchase order later today,” was his instant reply. I wished I had asked for a higher price.

One of the ladies in Farinon’s sales department tutored me on how to handle an international transaction. She said I should ask for an Irrevocable Letter of Credit for the purchase price. After CRC sent me the documents, I dumped the program from the NCSS computer on punched cards and shipped them to CRC. Joyce and I used the money to finance a Volvo station wagon.

A week later, an irate programmer phoned from CRC. “We’re having trouble installing this program on our IBM computer,” he began. “There are no comments in the program, no flowcharts, and no code documentation. Who wrote this mess?” he asked, not knowing he was dealing with a one-man operation.[*Non-executable statements placed in the program’s code to explain the functions of key sections.]

My ego was hurt, but we had already spent the $1,500, so I had to accommodate him. “I’m sorry, he is not available. Perhaps I could help you,” I offered.

“We cannot solve this through the phone. We’ll need someone up here,” he barked at me.

After I calmed him down, CRC agreed to pay the expenses to fly me to Ottawa for the weekend. Without revealing that I wrote the program, I was able to help iron out the problems in one day. Only years later, after I hired professional programmers, did I learn the proper ways of documenting the source code of a large computer program.

Once the engineers at Farinon became proficient with the computer-aided design, I took on new project responsibilities. I developed several components for a new microwave repeater. [*Microwave signals propagate in straight lines and do not follow the curvature of the Earth. Receiver-transmitter combinations are required at 25-30 mile intervals of a long-haul communication system to pick up and retransmit the signals at slightly different angles.] When they were completed, I wanted to learn about the entire system. I had always worked on the components, but knew very little about the complete operation.

My manager agreed that I could take a one-week short course on microwave radio system design at the continuing education division of UCLA. I flew to Los Angeles for the class.

Shortly after the course began, I realized that most of the other students already knew what I wanted to learn. They were military defense experts coming from companies like Hughes, TRW, and Aerospace. Their interest was in how to communicate between rapidly moving objects, such as two fighter planes. I only wanted to know how to send and receive signals between two stationary antennas placed on the Earth.

Fortunately, the teachers reviewed the basics at the beginning. The next day was spent on microwave filters, a topic which interested me. After the second day, however, I was lost. For the next three days, most of the material went way over my head. By the end of the week, I had developed the utmost respect for those who designed our nation’s military electronics defense systems.

During the course, I met the chairman of the Electrical Engineering Department, Gábor Temes, who was another 1956 Hungarian refugee. I told him about my involvement in computer-aided design. “Why don’t you create a short course on that subject and teach it at UCLA?” he asked me.

“I don’t have a Ph.D.,” I replied.

“That’s not a problem. The man who taught the filter section in the course you’re taking doesn’t have one either,” he said. “But both of you have much practical experience in the subjects. You could teach the course together.”

I thanked him for the advice and talked with the filter expert, Bob Wenzel. We had dinner that night and agreed to develop a course. He would cover two days on microwave filter synthesis, [*A closed-form mathematical procedure to find the exact component values of circuits that pass and reject specified frequencies.] and I would follow with three days on microwave amplifier design. Both of us would emphasize the computer-aided approach.

I realized that such a course would serve as a hidden advertisement for COMPACT, so I was eager to pursue it. My manager was shaking his head in disbelief when I told him about my idea. “Perhaps you should cut back to work only half-time at Farinon instead of killing yourself,” he suggested. “You already work more than anyone I know. Why would you want to take on more?”

Later that day, Bill Farinon called me into his office. “I am concerned about you,” he began. “Why don’t you take a three-month leave of absence? See if your business has a future. If it does, go at it full time. If it doesn’t, come back to work here and forget the rest.”

He was absolutely right. My heavily packed schedule couldn’t bear the addition of even one more project. I needed to make a decision—one way or the other.

My father-in-law was not happy to hear that I was considering leaving a steady job with a good company. Because Joyce was expecting our second child, he was concerned about my medical insurance. “This may not be a good time to be on your own,” he told me. “Don’t be so impatient. Frankly, I don’t see how anyone can make a living by selling a computer program!”

This time, I did not take his advice. At the beginning of 1976, after adding another room to our house, I incorporated Compact Engineering and began to work full time at home. I was the president and treasurer of the company, and Joyce was the secretary. Perhaps to make sure I would not go broke, my father-in-law agreed to become a board member.

We expected our second child in June. I applied for medical insurance at one of the major companies. Their questionnaire asked about my family’s past medical history, and I entered the information about the tests George had undergone at Stanford two years earlier. A few weeks later, the company accepted Joyce and me but rejected our son.

The news hit us hard. Perhaps the Stanford physicians had not told us everything. What if George has a serious heart disease? I immediately went to Stanford to inquire. “Please tell me the truth,” I pleaded with the doctor.

After looking through the initial test results and the follow-up examination records, the doctor again assured me that George absolutely did not have any heart defect. “Would you write a letter to the insurance company and tell them that?” I asked him.

The doctor’s letter did not change the insurance company’s decision. I applied to a different company, and this time did not mention George’s tests. All three of us were accepted, but we lived with the fear that if we made a major claim the company might recheck our initial information. Fortunately, none of us had any serious health problems.

In 1976, the IEEE’s microwave society (MTT) held its annual symposium in Palo Alto. For the first time, the event included exhibits, and I rented a booth there to publicize COMPACT. My booth did not have large fancy signs and displays. Instead, to attract potential customers, I offered a drawing with a Polaroid camera for a prize.

My booth was located in the middle of one of the aisles. I stood in the booth next to a small sign and planned to hand out the lottery sign-up sheets to everyone passing by. The idea was good, but I had overlooked the importance of sex appeal.

Facing the direction of traffic flow, at the end of the aisle in the wide booth of Company X, three provocatively dressed young ladies were handing out shopping bags with the company’s logo on them. The men I had planned to attract to my booth never noticed me. They passed by, rushing to have a closer look at those ladies. My great promotional plan ended with only a handful of new contacts.

|

Left: The top part of my home-made magazine advertisement of COMPACT. Right: Low-budget signs in my booth |

After my disappointment at the symposium, I decided to advertise in the trade magazines, but they were expensive. Finally, it became obvious to me that teaching short courses would be the ideal form of promotion. Instead of paying for advertising, I would be paid as an instructor, and all the students would be exposed to COMPACT. If they learned how to design microwave circuits with my program, most likely they would want to use it again after returning to work. I asked Bob Wenzel to put full-time effort into developing the material for his portion of the UCLA course. I began to do the same.

We decided to use the title “Microwave Circuit Design” for the five-day course. Preparing the overhead transparencies for my three-day portion of the course took a considerable amount of time. In the pre-Microsoft Powerpoint era, all text and illustrations of the artwork first had to be created manually. On some of the pages, I also inserted the results of COMPACT’s runs. Using a copy machine, I made the overhead transparencies I would use in the presentation. After rehearsing my talk, I settled on showing about 80 pages for each day.

UCLA promoted the course heavily by direct mail to companies and individuals. The response was overwhelming. Six weeks before the start date it was fully booked, and the school scheduled additional sessions. Their East Coast educational partner, the University of Maryland, also asked to present the seminars at their locations. Companies began to ask for in-house presentations. Creating the short course turned out to be a highly profitable investment of my time.

Bob and I recognized that maintaining students’ interest in a five-day microwave design course would not be easy. Microwave theory is abstract and mathematical, so we agreed to focus on the practical applications as much as possible. In addition, we planned to make the course lively by occasionally telling anecdotes about our own careers. One of them described my first experience of submitting an article to IEEE Transactions.

A year earlier, Professor Newcomb and I had written an article for the trade magazine Microwave Journal to describe COMPACT’s structure and capabilities. The subscribers to that popular periodical had a wide range of technical backgrounds. To clarify some of the new concepts to the novice, without boring the more experienced readers, we included several sidebars with detailed explanations. We used plain language throughout the article.

Just as we prepared to submit it to the magazine, we learned that a prestigious IEEE publication planned to release a special issue on computer-aided design techniques. Being published in that professional engineering society would be a real status symbol. Though I had never written anything for them, we changed our plan and sent the article to its editor. In a short time, a rejection letter arrived. “No significant technical contribution,” was the reason given.

I was crushed. My coauthor, who had significant IEEE publishing experience, tried to console me. “The article is too straightforward,” he said. “We’ll have to make it more complex. Let’s rewrite it!”

We did just that. First, we removed all the sidebars. Next, we replaced many of the short words with longer, more impressive-sounding ones. Finally, we changed the variables “a” and “b” in the equations to the Greek symbols α and β. When it was resubmitted in all its convoluted glory, the article was accepted and published!

I frequently used that example to amuse my students. Then I showed them a couple of slides to illustrate my story. The basic material came from an unknown source. I added the parts about the IEEE.

|

I was right. The students were highly amused.

The first Microwave Circuit Design course we presented at UCLA was also educational to me. Bob taught the first two days, and I followed him with three more days. By Thursday afternoon, the students looked exhausted, and I sensed that we had a problem. We struggled through the last day.

After the course ended, Bob and I looked through the written evaluations from the students. They liked the material but felt that we had packed too much into five days. “This course should be two weeks long,” said one. “I wish we had practice sessions to apply what we’ve learned,” stated another. “You advocate computer-aided design, but we did not have the opportunity to use a computer,” he added.

Based on the feedback, we reduced the amount of material covered. UCLA agreed to let us use their computer classroom for one afternoon of each course. They installed COMPACT on their system for the next course. The students learned how to use it and had the opportunity to design circuits with it. At the end of that course, Bob and I received outstanding reviews.

UCLA was happy with the success of the course. Bob and I received 25% of their tuition revenues, amounting to more than $2,000 for each day of instruction! In addition they also paid our travel and hotel expenses. On top of all that, several of the students began to use COMPACT through timesharing, which increased the royalties. Last, but not least, the thousands of brochures UCLA mailed out served as an indirect promotion for the program. Even if the school had not paid me a dime, I would have benefited from the teaching.

My mother was very impressed to know that her son taught at such a prestigious American university. Teachers were highly respected in Hungary. On my next visit to Budapest, she introduced me as a professor, rather than an engineer. I did not want to take her joy away and went along with her story.

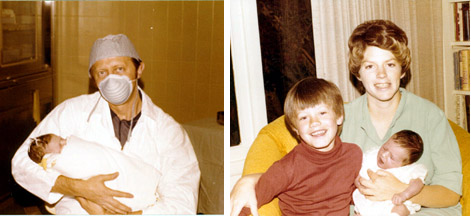

On June 4, 1976, my wife gave birth to a beautiful healthy daughter, Nancy Ann. That time I was in the delivery room and had the opportunity to hold the tiny baby immediately. The photo one of the nurses took of the two us shows my happiness on the occasion.

Joyce and I had been warned prior to Nancy’s arrival about the possibility that George might resent losing his status as the only child at home. “He has been the undivided center of attention for five years. He may be jealous of the newborn child,” said one of the neighbors. “Be careful how you treat them.”

As it turned out, George was delighted to have a little sister. He spent hours caressing and talking to her. It was no accident that Nancy’s first word was, “Geooooorge,” instead of Mommy or Daddy.

|

Left: A proud father with his newborn daughter. |

Joyce had her hands full taking care of the two children. To replace her function in the business, I hired the daughter of a neighbor to become Compact Engineering’s first employee. I also found a microwave engineer who was interested in programming. I hired him and he helped me to write code for new features added to COMPACT.

The two extra people working in our house made it crowded. The idea of finding an outside office, however, did not appeal to me. I enjoyed working at home, next to my family. In the spring of 1977, we looked around and found a solution—a large three-level house being constructed on a slope in Los Altos Hills. The rear side of the house overlooked a peaceful valley. Its 1,200-square-foot basement would be an ideal office. I could maintain a short commute to work—20 steps downstairs.

The beautiful house was nearly finished, and the contractor told us we could select the interior finishes and appliances. When George spotted the large closet under one of the stairways, he was ecstatic. “Let’s move here,” he pleaded. “This could be my fort!”

We sold our first house with a 200 percent capital gain and purchased the home in the hills for $200,000. Now I had to make more money to pay for our fancy new place.

|

Our new mega-home in Los Altos Hills, before the landscaping |