Through 1976, demand for COMPACT was increasing. By the following year, we had six employees. George began first grade, and Nancy frequently came downstairs to entertain us. She loved to sing to her captive audience and could not understand why I had to take her upstairs instead of asking for encores. Even though the children sometimes interrupted my daily routine, I was glad to be so close to the family during work. I felt that my presence made up for the times when I had to travel.

Somewhere I had heard that when children suffer minor injuries, the fastest cure is to take their attention away from the pain. I found a successful way to apply that theory that always worked with our daughter. It involved the neighbor’s dog.

Beyond a chain-link fence at the bottom of our sloping backyard, a large German shepherd watched over our neighbor’s property. His name was Max. One day, while Nancy was running by a rose bush behind our house, a thorn pricked her finger. She began to cry so loudly that I could hear it inside my office.

When I rushed out to investigate, she showed me the tiny drop of blood on her finger. My efforts to calm her did not work. She cried even harder. Max stood on the other side of the fence, watching the drama.

In desperation, I picked up Nancy and carried her down the slope. “Let’s tell Max what’s happened,” I suggested. She immediately stopped crying.

When we reached our side of the fence, I talked to Max. “Look at Nancy’s finger,” I said. “Could you make her feel better?”

Max wagged his tail, and I kept talking to him. Nancy also told him what that awful bush did to her finger. She completely forgot about crying. We said good-bye to Max and walked back to the bush. I spanked it for its crime. The matter was closed.

From that day on, I used the distraction technique successfully many times. It even worked when we were away from our house. Whenever she was hurt, l promised to tell Max as soon as we arrived home. Of course, I always had to follow up on my pledge. Max was a wonderfully sympathetic listener. As payment for his healing services, I sneaked him daily treats.

In the 1970s, only a few of the AYSO coaches in our soccer organization had actually played soccer. I felt that with my experience the best assistance I could provide was to teach new players the basics. In those days, children began playing on teams at the age of five or six (now they start at age two). After George began first grade, I enrolled him on the team I was coaching that year.

My wife and I were still concerned about his face turning red after hard running. On a soccer team, the goalie rarely runs, so that was the position I selected for George. My only concern was that even if a goalie makes several spectacular saves, everyone remembers when he misses the ball. Fortunately, George turned out to be a good netkeeper and enjoyed his teammates telling others about his performance. I was happy that he could participate in a team sport without putting stress on his heart. Later, we learned that the murmur was gone, and we no longer had to be concerned about his health.

I was fortunate to find key employees to share my workload and enhance our professional image. Mike Ball, an outstanding programmer, restructured COMPACT and added the much-needed comment lines. Chuck Holmes, one of the most capable engineers I have ever met, helped to lighten my travel schedule. He took over the program’s in-house installation and training, leaving me with marketing and teaching the university short courses.

Instead of running my amateurish ads in the trade journals, I submitted technical articles to the journals. That did not cost money, and the articles served as concealed advertisements. I also encouraged our customers to publish their success stories. By the third year of our full-time operation, COMPACT was recognized as the industry standard.

The Defense Department had strict guidelines for exporting goods that might be used for military purposes against NATO. Most of the military communication and weapons guidance systems operated at microwave frequencies. COMPACT was often used to design the circuitry of those systems. Accordingly, the Eastern Bloc countries and other potentially hostile nations were on the blacklist. Although I was extra careful in screening the customers, there was one time the program ended up in the wrong hands.

A British trading company ordered COMPACT and stated it would be used by one of their divisions. They transferred the funds to us, and we shipped the program to their address. A few weeks later, they asked for installation assistance, and I sent Chuck over for the job.

Nearly a week passed without any news from Chuck. I became concerned and called London to inquire. “Your program was forwarded to one of our associates in Yugoslavia,” the company’s buyer informed me. “It was already running on their computer, but they needed help to tune it for maximum efficiency. Dr. Holmes has been working with them all week and should soon be finished.”

Yugoslavia was not technically part of the Eastern Bloc, but the West did not trust Marshall Titos regime. [*Long-time President and Supreme Commander of Yugoslavia. Although he initially sided with Moscow, in the late 1940s he switched to an independent form of Communism called “Titoism.”] He supported the policy of nonalignment between the two hostile blocs in the Cold War but conducted business with both sides. Even though the customer signed an agreement that the program would be installed only at one location, there was no guarantee that it would not be passed on to the Soviet Union. I faced a potentially serious dilemma.

If I told the Defense Department what had happened, who knew what the consequences would be? They could fine me or quite possibly even shut down my company. I decided to do nothing and anxiously waited to hear from Chuck.

A few days later, the head of the British company telephoned. He apologized for the extra time our employee had been required to stay and told me that Chuck was already on his way home. Their customer would of course pay us for the extended days required. He explained that he had been away when the decision to purchase COMPACT was made. In his absence, one of his subordinates had handled the arrangement. Supposedly, he was unaware that the end user was in Yugoslavia. I was furious listening to his lame excuse, but it was reassuring to know that our engineer was safe and would be back soon.

I picked Chuck up on his arrival at the San Francisco airport. On our way home, he described his adventures.

The morning he arrived in London, a representative of the customer met him at the airport. The man informed him that the work would be done near Belgrade at a non-profit research company. He had reserved a first-class flight for our man to Belgrade later that morning. Naturally, Chuck was surprised about the change of plans, but the representative assured him it had all been cleared with me. Not wanting to call and disturb me in the middle of the night in California, Chuck boarded the plane and enjoyed the first-class treatment.

A Yugoslav army officer waited for him in Belgrade. After a long ride in a military vehicle, they arrived at an army base. The commander, a colonel who spoke English well, welcomed him and the two of them had dinner together.

During the meal, the Colonel explained the problem. Their base had been designing military electronics, and they wanted to use COMPACT in their work. Their programmers, however, could not install the program on their Soviet-made Ural-2 mainframe computer. That is why they had asked for someone from our company to come and help. “I expect you to stay as long as it takes,” the Colonel emphasized. “We have very comfortable living quarters for you.”

When Chuck asked if he could call me, the Colonel shook his head. “I’m sorry, but for security reasons that’s not possible. I’ll ask our buyer in London to pass on a message for you.” (I never received a message.)

After dinner, a soldier led Chuck to a nicely furnished apartment and locked the door from the outside. Peeking out through the window, he could see an armed guard standing nearby. Accepting his fate, Chuck went to sleep. The guard unlocked the door at the start of each day and locked it again every night.

Chuck was a runner and he expressed his desire to jog every morning. The Colonel agreed. A soldier in a Jeep drove alongside, escorting him on the inner roads of the base as he ran.

The Soviet computer had an unfamiliar operating system. Many of COMPACT’s functions required complete recoding. Chuck worked long hours with the help of several capable programmers. He told me that at the time he was not sure if they would ever let him go. When the work was completed, the Colonel and his staff honored him at a special celebration. The next day, he headed home.

Hearing how the British company had deliberately misled us made me extremely angry, but it was too late to do anything. For a long time I lived in fear, dreading the consequences that might arise from that questionable sale. Fortunately, none did.

I promised myself to be more careful about future direct sales. After that incident, I modified our purchase agreement form to show specifically the location and detailed information about the computer on which the program was being installed.

I later changed my mind to this position, as follows:

These days, the end user never receives the source code of a program. Instead, the software companies create executable modules from their own computers. These modules must be registered by the user, usually through the Internet, to prevent usage on multiple computers.

In my business, however, I did not own a computer and could not generate executable code. In the 1970s, COMPACT was installed on the timeshare systems’ mainframe computers that were made by IBM, Control Data (CDC), Honeywell, CRAY, XEROX, and Univac. For my in-house sales, depending on the type of computer owned by the customer, I created a copy of the program’s source code on punched cards or magnetic tapes.

At the customer’s site, the source code always required modifications, because each of the timeshare companies had its own customized operating system and programming functions.

I had no real copy protection other than trusting the integrity of the buyer. Software pirating in those times fortunately was not what it is today. Of the several hundred direct COMPACT sales, there were only two cases where I suspected unauthorized usage.

A man speaking with an Asian accent called the office one day. “My name is Nobu Kitakoji,” he said. “I’m the president of Tokyo System Lab and would like to represent you in Japan. May I come to your office to talk about it?”

I did not know how to respond. He thinks I have a real company. I should not meet him in our house. “Let me suggest a restaurant where we could talk over lunch,” I said.

“Thank you very much, but if possible I would also like to see your operation,” he replied.

I could not think of any reasonable excuse not to have him visit us. I explained that my office was in my home. He sounded surprised but assured me it would not be a problem. Within an hour, he showed up at our front door.

Our visitor was slightly built, about five feet six inches tall, with a humble and polite demeanor. After bowing deeply from the waist, he offered to shake hands, contrary to Japanese custom. I introduced him to my wife, and we sat in our spacious living room to talk. He apologized for interrupting my schedule. Next, he complimented us on our house and admired the magnificent view of the valley. Then, he revealed a gift for me—a beautifully framed picture of Mount Fuji. His courtesy was almost overwhelming.

After a few minutes of general conversation, he turned to business. He had heard that some of the companies in Japan were using COMPACT through timesharing and asked if we had sold any for in-house installation in that country. I answered, “No.”

“Japanese companies will not buy foreign-made computer programs without having local representation,” he told me. “With our established contacts in the industry, however, I’m certain that we could sell quite a few programs for you.” He showed me his company’s customer list, which included familiar names like Sony, Fujitsu, NEC, and Toshiba.

In a short time, we came to a verbal agreement for his company to represent us in Japan. A few weeks later, he returned with his vice president to finalize the contract. After we signed the papers, Compact Engineering had its first sales representative. The arrangement worked out extremely well for us.

|

Meeting two officers of Tokyo System Lab. |

When the Space Communication Group of Hughes Aircraft Company purchased COMPACT, they asked me to conduct weekly four-hour tutorial seminars during an eight-week period. The company wanted their engineers to participate on their own time, so they scheduled the seminars from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. on Wednesdays. I flew from San Jose to Burbank in the early afternoon on those days and returned in the late evening. Hughes provided a driver to shuttle me between the Burbank airport and the plant.

In 1978, the San Jose airport had only one terminal with about a dozen boarding gates. The open-air short-term parking lot was just across the roadway. Security was almost nonexistent. With a ticket in my hand, I could arrive in my car at the short-term parking area 15 to 20 minutes before departure, walk to the gate, and board the plane. That specific Burbank flight always took off from the same gate. After the first couple of weeks, I was completely familiar with the routine.

One Wednesday, as I sat in the plane that was taxiing toward the runway for takeoff from San Jose, a male voice came over the PA system. “This is your captain speaking. Let me welcome you on our flight to LAX…”

“Someone better tell the captain that we are going to Burbank,” I said with a smile to the passenger sitting next to me.

“No,” he replied. “We’re going to Los Angeles.”

PSA had switched gates that day. I was on the wrong plane!

Fortunately, we were headed in the same general direction. As soon as we landed at LAX, I called Hughes from a pay phone and explained what had happened. I took a taxi and arrived at the plant just in time to begin the course. The students enjoyed hearing what an absent-minded professor they had, but it was not a mistake I wanted to repeat.

I always checked gate assignments after that day.

In January 1979, a man called me. “My name is Wayne Brown,” he said. “I am heading up a new project for Communications Satellite Company (Comsat) and want to know if we could come to a special arrangement with you. Let’s have dinner together to discuss it.” We set up a meeting at Maddeline’s in Palo Alto for a few days later.

Although Comsat Laboratories in the Washington D.C. area was on our user list, I did not know much about the company. The financial brochure our stockbroker gave me the next day, however, provided quite a bit of information. The company had been formed as a result of the U.S. Congress Communications Satellite Act of 1962 and had been incorporated as a publicly traded company in 1963. Satellite communications were performed at microwave frequencies, so we had something in common. I was eager to learn what they wanted from me.

Mr. Brown and I arrived at the restaurant the same time. The owner, whose son played on my AYSO soccer team, recognized me as the two of us walked in. He led us into a small private dining room. At first, I thought that we were receiving special treatment because of my coaching, but later I learned that our reservation had been made for that room.

The Comsat man did not waste time. As soon as we were seated, he told me that a few years previously, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had reclassified the company as a utility and began to regulate the rates it charged to its customers. As a result, Comsat’s revenues and profits had begun to decline. To make things worse, the company’s worldwide monopoly on satellite telecommunication was to end the following year with the new Open Skies Policy of the FCC. The new ruling encouraged competition. Comsat’s management had decided to diversify and look for new business ventures. One of their ideas was to automate the engineering design and manufacturing processes of high-tech companies.

“This is why I wanted to see you,” he said. “The engineers of the large companies either use outside timesharing or their own central mainframe computers. The first alternative is expensive and not fully secure. In the second case, they are using a computer that was purchased for business instead of scientific applications.”

I did not see where he was heading. “True, but are there any alternatives?” I asked.

“Not yet,” he replied. “Within a year, however, my group will develop a new design system running on minicomputers. We’ll automate the engineering departments. Digital Equipment (DEC) and Prime Computer Company have recently introduced powerful minicomputers that are capable of handling the needs of 30 to 40 engineers simultaneously!”

In my business, I focused on mainframe computers and was unaware of the minis he mentioned. All of a sudden, I became interested in his project. “Tell me more.”

He would not go further unless I signed the nondisclosure agreement he had brought with him. I signed on the spot. Then he outlined his ambitious business plan.

His group of 20 professionals had been converting various business applications, such as database management, word processing, and something new—an “electronic spreadsheet” called VisiCalc—to minicomputers. Next, he wanted to add COMPACT to the package. “We’ll sell the entire turnkey system to companies who are in the military defense and telecommunications business. You’ll make more money because we’ll market your program,” he said.

He predicted that customers using their system could drastically reduce engineering administrative staff. “Right now, when you need a letter, you dictate it a secretary who types it. If every engineer has a computer terminal and learns how to use it, there’ll be no need for secretaries.”

The man sounded like a visionary. The more I heard, the more excited I became. Under his proposal, Comsat would pay us generously for the conversion and sign a non-exclusive license to market COMPACT on the minicomputers. They had leased a large building in Palo Alto, and we could share the facilities with his local group and have access to their minicomputers.

The idea sounded attractive. At that point, Compact Engineering had ten employees, and it was time to move out of the home office. It would be ideal to use their building for six months, until the estimated completion of the project. By then, I would have found a new office.

I gave Wayne a tentative positive answer. Back at home, I discussed the offer with Chuck, Mike, and my wife. All three thought it was a great opportunity to expand the scope of our business. Joyce was also happy to regain the exclusive use of our kitchen. Within a few weeks, I signed a firm contract with Comsat and moved into their building.

Our children did not like the change. Nancy had just begun preschool and would cry in class. “My daddy started to work, and he’s not home anymore during the day,” she told the teacher. When the teacher asked her how long I had been out of work, she said, “He’s never worked.”

A few days later, I met the teacher. “I’m so glad to hear that you’ve found a job,” she told me. “But apparently Nancy does not like the change.”

I was confused. “I’ve been working full time since I turned eighteen. Where did you hear that I did not have a job?”

“Nancy said that you’re no longer at home during the day,” she replied.

I finally understood and explained to her that I began my home business the year Nancy was born. To Nancy, a dad who was at home during the day couldn’t possibly be “at work” at the same time!

Many of the Comsat employees in the local group came from Hughes Aircraft. Most of them had programming backgrounds, although there were also a couple of engineers. They were highly competent ,and we quickly developed an excellent working relationship with all of them.

Maintaining a program with over 20,000 lines of code had become difficult. We had the listings of the programs from about 60 on-site installations. When a customer reported a bug, we first had to determine if it was unique to that installation or if it existed in all programs. As the number of in-house installations increased, the required product support was becoming unmanageable.

At that point, our direct sale revenues far exceeded our timeshare royalties. It was clear to me that once the program became available for minicomputers, even small companies could afford to buy it. I decided to focus on that market. To differentiate the new program from the previous product, I assigned it the name Super-COMPACT. Our programmers placed clever software switches into the code to eliminate the need for storing the listings of all future customers.[*Statements to separate program segments unique to specific customers.]

Although we had gradually increased the program’s price from $1,500 to $10,000, Wayne laughed when he heard the latter figure. “You’ve been giving away that program,” he told me. Comsat’s market analysts recommended selling Super-COMPACT on the minicomputers for $60,000! I was horrified to hear that price, but time proved them right. I had been giving away the program!

Two months later, I proposed to Wayne that we expand the scope of their design system by letting my company add two other circuit design programs: SPICE from UC Berkeley and FILSYN, a major filter synthesis program. The SPICE program had been developed with public funds, so its source code was available at no cost. The filter program was owned by an individual I knew well, and he was open to the idea of joining us. Both programs were running only on mainframe computers. Therefore, they would require extensive conversions to run on the minicomputers.

Wayne liked the idea, but such a significant modification to our original agreement required the approval of a Comsat vice president. Our plan was accepted, and I added five more people to the Compact staff to work on the two programs. With 15 employees on our payroll, I had to pay more attention to personnel issues. To minimize my administrative workload, I split our technical people into two groups. Chuck headed our engineers, and Mike was responsible for the programmers.

As our project completion approached, I read a lengthy article in Business Week. According to their prediction, office automation would become a five-billion dollar business within the next five years. If that is true, IBM, General Electric, HP, and other giants will enter into that business. They will squash Compact Engineering! What should I do?

I called for a conference with both our accountant and our corporate attorney. “Would Comsat be interested in buying your company?” asked the accountant after hearing my concern.

I had not thought about that, but the management style of Comsat did not appeal to me. The fact that the U.S. government had created the company had left its mark on it. Lower level managers had limited decision-making power. Critics often referred to the company as a “government corporation.”

Comsat was also quite formal, placing importance on titles and academic degrees. It was something I had never liked at Fairchild, where those with Ph.D.s were always addressed as “Dr.” by their subordinates. I preferred the style at HP and Farinon where virtually all employees were called by their first names.

On the other hand, Comsat was a large company that could provide protection. Its worldwide sales and marketing organization could do a far better job selling our products than I could. The company had an expressed desire to diversify due to the loss of its satellite communication monopoly. I concluded that the good outweighed the bad and that it would make sense to explore the possibility of selling Compact to them.

Our accountant recommended a two-day seminar titled, “Selling Your Own Business.” I attended the course in San Francisco the following week. It was an eye-opener and helped me to formulate a strategy for selling the company. That opportunity came faster than I expected.

Halfway through the Super-COMPACT installation on the DEC PDP-10 (VAX) minicomputer, Wayne and I flew to Washington D.C. to give a presentation to a small group of Comsat officers. We met in the president’s luxurious private office on the eighth floor of their headquarters located at L’Enfant Plaza. The wide windows of the office offered a spectacular view of the city’s landmarks.

During the luncheon that followed the meeting, their vice president of marketing sat next to me. “At what price should I be selling Super-COMPACT to companies that already have a VAX?” I asked him.

He stared at me. “I thought we had an exclusive arrangement with you to market the product,” he said.

“Your exclusivity only applies to bundled sales,” I replied. “I have the right to sell the program without a computer.”

The news must have spoiled his appetite. It appeared that he had the wrong information. “That’s going to be a problem,” he said after some thought. “Let me talk this over with Mickey Alpert.” He stood up, walked over to the other side of the table and began a conversation with another man. “Let’s talk about this after lunch,” he suggested when he returned.

Mickey turned out to be the vice president of mergers and acquisitions. He set up a meeting for later in the afternoon. “Would you consider a merger between Comsat and Compact Engineering?” he asked, after I had answered several questions about my company.

I remembered the final advice given to the participants at the conclusion of the recent business seminar: Let the buyer pursue you! “I haven’t thought about it,” I replied, while trying to hide my excitement. “Our employees like the small company environment.”

“You could certainly maintain that environment. I know you operate differently in California. Don’t let our ways here scare you,” he assured me. “Think about it after you go home. Comsat’s resources would help your company grow much faster.” I promised to reply in a few days.

Wayne told me that he was asked to stay there for another day. After my return, I contacted Owen Fiore in Los Angeles to find out if he would represent me in a possible merger. He was one of the attorneys who had lectured in the San Francisco seminar, and I had been impressed by his presentation. “I’ll be up in your area over the weekend,” he told me. “We could talk about it then.”

Wayne called me at home the next evening. “Let me come over and tell you what Comsat is planning to do.” Knowing that it must be something important, I agreed. He was at our house in a few minutes.

“With my group’s recommendation, Mickey has already been negotiating to purchase a small Texas company that has an outstanding digital design program,” he began. “When that acquisition happens, it’ll fill the only missing link of our design system.”

He was right. Our programs only handled the analog portion of a system. Adding a capable digital design program would make the Comsat package highly marketable. However, Wayne was not finished.

“If that deal goes through and you also agree to sell, Comsat would set up a new West Coast subsidiary, headed by me. It would have multiple divisions: the Compact group led by you and the digital group with its current president,” he added.

It sounded like Comsat was serious. I told Wayne that I was interested and planned to meet with an advisor to discuss it over the weekend.

Owen Fiore spent Sunday morning with me. After looking at our financial records, tax returns, and customer list, he agreed to represent me. In addition to expenses, his charges would be based on the time spent on the case.

As for the sales price, he felt that it should be equal to our revenues from the past twelve months. Instead of cash, he recommended that we ask for a tax-free stock exchange. “When the news that Comsat is entering into the office automation market reaches Wall Street, the stock price should go up,” he said.

I phoned Mickey the next day to follow up on our conversation. He flew to California and stayed in our office for an entire day. Before he left, I signed a letter of intent to merge that he took with him to present to Comsat’s board the following week. The ball was rolling.

During the following weeks, I visited Comsat headquarters twice. The first trip was mostly spent on technical discussions and planning. The second time, Owen also came with me to talk about the financial terms. I was glad to have Owen there, because he asked for a wide range of benefits that would not have occurred to me. By the end of our second visit, we reached a tentative agreement with Comsat that only needed their board’s approval and a satisfactory audit of Compact’s financial records. One of their business managers and a CPA were to come home with us to conduct the audit.

The terms of the agreement far exceeded my expectations. I would be a senior vice president of Comsat and president of the Compact Division, with an annual compensation over $100,000. In addition to a four-week paid vacation, I would be paid for an additional four weeks during which I could teach university courses and keep the revenues received. The executive benefit package included fully paid medical and dental insurance for me and my family; life and disability insurance; and a company car. For retirement consideration, Comsat would give me retroactive credit for my employment with Compact. Along with our two key employees, Chuck and Mike, I would receive a five-year employment contract. Compact and Comsat were to each pay their own legal expenses for the merger.

On the flight home, I reviewed our personal finances. The 35,000 shares of Comsat I would receive in exchange for my company’s assets would pay annual dividends of $2 per share. When I added everything up, both my income and net worth would be higher than my father-in-law’s. Only a few years earlier, my annual salary at Farinon was $30,000 and we had lived well on that. Now, we would have so much more. Never in my life had I expected to achieve such wealth.

A few days after going through Compact’s financial records, the Comsat business manager asked to have a private conversation. “You must keep what I have to say between the two of us,” he began. “Comsat would fire me for disloyalty if they found it out.” I promised full confidentiality.

“Your company has high potential, but Comsat is not flexible enough to take advantage of it. Don’t sell out now. Hire me to be your business manager. We’ll look for outside financing and grow the company for a couple of years. Then we’ll go public.”

I was astonished to hear what he said. “How could I do that after already signing a tentative agreement?”

“The merger hasn’t been finalized. You can always back out before the formal agreement is signed.”

His proposal sounded unethical. After negotiating a deal with Comsat in good faith, how could I turn them away now? On the other hand, going public in a few years sounded lucrative. I called my father-in-law and Owen for advice. Neither of them wanted me to hold out.

I had the impression that Owen was more concerned about the possibility of losing the additional revenues than the ethical part. My father-in-law, on the other hand, agreed that I should not trust someone who was ready to “bite the hand that fed him.” I valued his opinion and decided to go with Comsat as planned.

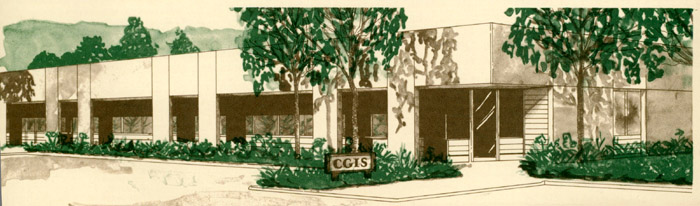

It took about a month to finish the transaction. Just before Christmas 1979, we signed the final agreement. Comsat established a new subsidiary called Comsat General Integrated Systems (CGIS) and changed the name of my division to Compact Software. They purchased land near the intersection of San Antonio Road and Hwy 101 and proceeded to build a new facility for the subsidiary. Our plant included a central computing center with a Digital Equipment VAX and a Prime 450 minicomputers, as well as a terminal on every employee’s desk. The recently purchased Texas group also became a part of CGIS. We began an aggressive hiring campaign to build a company that would automate engineering departments throughout the world.

|

Our new building in Palo Alto. Comsat built it to our specifications, although it took some time for them to agree to having a bicycle storage room. |

When we released Super-COMPACT in 1980, the demand for the program was overwhelming. Our advertising campaign emphasized that it would be offered only on the VAX. The key point was to decentralize engineering departments by offering a smaller computer center dedicated to scientific applications. Our motto was to have a computer terminal on the desk of every engineer. In 1980, that was a revolutionary new idea!

|

As our software complexity increased and computer displays became more readily |

A week after the program’s release, I received a call from an irate executive. He was the head of a division of Hughes Aircraft. “We are one of the most important defense contractors in the United States,” he shouted. “Who are you to tell me that I need to buy a minicomputer to use Super-COMPACT, when we have a multimillion dollar IBM mainframe in our central computing center?” He demanded that we make the program available for his computer.

I had learned at HP that “the customer is always right [*That was true in those times.] and gave in to his demand. We converted the program for his IBM. Soon after, General Dynamics wanted it on their CDC mainframe and the U.S. Military Research Lab wanted it on a Cray. We gave these companies what they wanted as well. Within six months, the program was running on five different computer systems. Although that made our support and maintenance more difficult, the customers were satisfied. Our business was booming.

Japanese companies that had not trusted a home-based operation also wanted the program from a Comsat division. I took frequent trips to Japan to speak at conferences and help with the promotion at trade shows. On my first visit, Kitakoji-san introduced me to eating sashimi—something I still enjoy.

|

Left: Our booth at a Japanese conference. Right: Participating in karaoke in a Tokyo bar. |

Back in California, the head of UCLA’s Continuing Education Center resigned and formed his own business. He offered short courses under the name of Continuing Education Institute (CEI). He asked if I would teach for his company at major industrial centers that would not compete with UCLA. I agreed to do it at two locations, in the Boston area and in Palo Alto. I especially liked the second post, because it did not require travel.

A Stanford-educated Swedish entrepreneur, Birgit Jacobson, established an overseas group, CEI Europe. Her philosophy was to offer courses at popular tourist locations where engineers would also take their families for vacations, like Nice, Barcelona, and Davos. She asked me to teach in Europe. I consented, because those trips would allow me to visit my mother in Hungary.

Engineers who had taken our introductory design course asked for an advanced level course. Since I didn’t have time to conduct more courses myself, I found other lecturers and designed a class to follow the one Bob and I taught. The two courses formed a strong foundation for high-frequency circuit designers. Three decades later, updated versions of the classes are still being offered.

In 1980, American Airlines began a passenger loyalty program, called AAdvantage. United soon followed with its Mileage Plus program. I flew frequently on both airlines and soon became a member of their elite classes, which enabled me to be in first class on most trips. That year I traveled about 30 percent of the time, so accumulating mileage in the programs was easy.

At home, I often performed “magic” tricks for our children. My favorite was to “change traffic lights.” When we arrived at a red light, I stopped the car and looked at the traffic light for the cross street. As soon as I saw it change from green to amber, I would say “Abracadabra kalamazoo, red light change to green!” The children, who watched only the lights facing our direction, observed the red change to green. They were always impressed by my magic powers.

One weekend, our three-year-old Nancy was invited to a sleepover at a friend’s house. “Daddy, can you really change the red light to green?” she asked me after returning home.

“Yes, of course,” I replied. “Why do you ask?”

She told me that the father of her friend had taken the girls out for a pancake breakfast. On the way to the restaurant, they reached an intersection where the traffic light was red. Nancy asked the dad to change the light.

“I can't do that,” said the father.

“My daddy can do it,” Nancy told him. “Perhaps he could teach you, too.”

I had no choice but to admit the truth. It took quite a while to regain her trust.

After buying a truck and a camper, my in-laws invited us to camp out for a weekend at a lake near Nevada City. The huge pine trees blanketing the area and the clear blue sky reflecting in the water presented spectacular scenery. Joyce and I fell in love with the area and purchased a large lot only a block away from Scotts Flat Reservoir.

My father-in-law thought of a joint project for our lot. He would buy a log cabin kit, if we assisted him in building it. We thought it was a great idea and agreed. After the lumber was delivered, we all took a week off to start the construction. My brother-in-law, David, also came with us. A local contractor provided guidance and directed our work.

I had never used a hammer for longer than a few seconds at a time. Hammering the large nails into the logs for a week lead to a sore elbow. The following week when I tried to play tennis, I had trouble hitting the ball. When the pain persisted, I went to see a sports doctor. He diagnosed a severe case of tennis elbow—developed during my week of being a carpenter. It was several months before I could return to playing tennis.

My brother-in-law and one of his college friends spent their entire summer vacation working on the cabin. After it was completed, my father-in-law purchased a powerboat and water skis. We all learned to water ski and spent many weekends in that area.

I enjoyed playing with my children when I was home, but my work required me to travel a lot. In mid-February, Kitakoji-san asked me to participate at the TokyoCom conference scheduled for the newly constructed convention center near Tokyo’s harbor. “I arranged a TV interview for you,” he informed me. “It’ll generate a lot of publicity for your company.”

I knew that he had arranged a booth for us in the exhibit area but had not been planning to attend that conference, because Joyce was so unhappy about my frequent travel. However, the idea of being interviewed on Japanese television appealed to me. Even with the short notice, I agreed to go.

I arrived in Tokyo in the midst of one of its most severe winters. To make things worse, the heating system in the exhibit area of the new convention center was not operating. We were extremely uncomfortable staffing our booth wearing only our business suits, but warm coats would have been culturally inappropriate in appearance-conscious Japan. We hadn’t thought to bring layers of long underwear. Our representative brought small chemical heater pouches that we could keep in our pockets, but it was not polite to keep our hands in our pockets. The only option was for us to stand shivering in our booth with forced smiles on our faces.

Although I had participated in other conferences in Japan, the TokyoCom was the largest and most interesting I had ever seen. The employees of the various large companies wore bright-colored business outfits. Most of the exhibits had high-power PA systems blasting their messages. Pretty young women stood in front of each booth, politely handing out company literature and gifts. Thousands of visitors strolled through the crowded aisles.

The five-minute-long TV interview in the exhibit area was very interesting. The reporter asked questions in English and repeated them in Japanese. He also translated my answers for the viewers. In my hotel room that evening, I watched his report on TV during the evening news. The effects of the chilly environment showed, and I did not look comfortable during the interview. However, it was good publicity for our company.

|

Left: Sampling Japanese snacks during the TokyoCom opening ceremony. Center: Setting up for the TV interview. |

I spent much of the flight back from Tokyo planning my family’s future. I felt that I had already surpassed all my professional goals and did not want to stay in the rat race much longer. After fulfilling the five years of my employment agreement with Comsat, at the age of 49, I intended to retire and leave the high-tech world. With the dividend income from our stock and the retirement benefits from Comsat, I calculated that we could live comfortably without any financial concerns.

The kids especially missed me during business trips, although they liked it when I went to Japan because of the unique gifts I always brought home. George was already nine years old and Nancy nearly five. During the previous year, not only had I moved out of the home office, but also I had traveled all over the world without them. To make up for the time I had missed with the family during my business trips, I was eager to fully devote myself to them. After retirement, I could find opportunities to coach both track and soccer. Perhaps I could also teach courses occasionally.

To my dismay, my optimistic plans were not to be carried out in the way I had envisioned. Within a few days of arriving home, I learned that my marriage was in trouble. The possibility of a divorce loomed, and I desperately searched for a way to prevent it. Our close friends and relatives were as puzzled by the news as I was. Joyce and I had seemed to be one of the model couples of the community.

I thought perhaps one of the issues between the two of us was the age difference, so I tried to look younger. Noticing some hair loss, first I had permanent waves added, and then a toupee. Cosmetic surgery was the last step. None of those physical changes brought any positive results in my marriage. It seemed that there were deeper problems of which I had been unaware. Marriage counseling did not provide any solution as to what I could do. Joyce was determined to end our 13-year marriage.

I could not help but think of my marriage breakdown in terms of a hurdle race. My track specialty had been the 400-meter hurdles, an event in which there there are ten hurdles to pass over. During my racing career, every time I reached the last hurdle I felt relieved, because there were no more obstacles on the way to the finish. Now, in my life’s race, I felt as though I had passed over the last hurdle, only to find that someone had unexpectedly snuck another one in my way.

As if my marital problems were not enough, difficulties with personnel began to interfere with our progress at work. For several months, our top technical employee had disagreed with the company’s business plan. Chuck, our vice president of engineering, wanted to add new features to Super-COMPACT before its release. The sales department wanted to sell what we had and market a new version later. Chuck’s stubborn stance created tension between engineering and the rest of the company. I had private discussions with him, but his attitude did not change. The president of CGIS recommended terminating Chuck’s employment.

I was torn between my loyalty to Chuck and my concern about the continued operation of the company. He was the first engineer I had hired, and he had been a major contributor to our success. He had always been a dedicated worker. To complicate the case, he still had almost four years left of his five-year employment agreement with Comsat.

When I presented the problem to our legal department, one of the attorneys made an interesting revelation. “We had serious personnel problems with an employee last year,” he told me. “Instead of firing him, we sent him through a program called Lifespring. In five days, he became a totally different person. He is still with the company.”

“What’s Lifespring?” I asked.

“It’s a humane version of EST." [*http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erhard_Seminars_Training]

I had heard that EST was some kind of mind-control process. Participants were locked into rooms for hours without even being allowed to go to the bathroom. If Lifespring was similar, I did not think Chuck would like it. I asked the attorney to find a legal solution to our problem.

That evening, I met with our daughter’s kindergarten teacher. Through the school parents’ grapevine, she had heard about my marital problems. She asked if she might offer a possible solution. I was eager to hear what she had to say.

“The parents of another of my students were recently considering divorce,” she began. “A mediator recommended an awareness course. After both of them attended, they worked out their differences and stayed married.”

“What kind of course was that?”

“Lifespring. They took it together in San Jose.”

Two different people had recommended the same thing to me in one day. It cannot be an accident! Perhaps it could help me find the solutions to my problems. “Thanks, I’ll look into it,” I told her.

The next morning, I called Chuck into my office. He seemed nervous and was probably expecting to be fired. I began as gently as I could. “You and I both know that we have a serious problem with your attitude. I’ve heard about a course that might help both of us. Would you go through it with me?”

He wanted to know more about the course. I told him the little I knew. He asked me to give him some time to think it over. An hour later, he came to see me. “Let’s do it,” he said.

The Basic Lifespring Program [*http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lifespring] was five days long. From Wednesday through Friday, there were evening sessions only, but Saturday and Sunday were full days. Chuck and I drove to the Holiday Inn in San Jose for the first session. Approximately 300 people were eagerly waiting outside the closed doors of the ballroom. When the doors opened, the Lifespring staff ushered us inside.

Promptly at 5 p.m., after everyone had been seated, the trainer introduced himself. Then he asked if we knew what the lowest form of awareness was. “Not knowing anything,” offered one of the participants.

“You’re close, but not right,” the trainer replied. “When you know that you don’t know, you’re already at a higher level. The worst case is when you don’t know that you don’t know.”

My interest perked up. I had never heard that kind of reasoning, but I agreed with him. This might be an interesting program. I’m glad we came.

The trainer went through the ground rules and some of these generated heated discussions. “The course will only start after you all agree to the rules,” he declared. “You must be seated every day at the agreed time. No one who comes late will be admitted,” was the first rule.

“What if I’m held up in heavy traffic?” “What if I can’t find parking?” participants asked.

“Figure out how to deal with those possibilities. Just be here on time!”

Some of the other rules were:

The leader encouraged participation. “Raise your hand when you have a question or want to share,” he said. “Wait until I call on you to speak.”

It took over two hours for everyone to accept the rules. Those who did not agree were asked to leave. Finally, the process began. Small-group discussions and exercises followed each one- to two-hour lecture. Each session was designed to handle a specific personal issue.

In the beginning of the first small-group session, the leader asked everyone to tell briefly what brought us to Lifespring. Like me, most people came after some traumatic experience in their lives—losing a loved one, having domestic problems, being fired at work, being sentenced for a crime, or just not fitting into society. One man came to overcome his fear of water. Our socio-economic backgrounds were varied; participants ranged from the unemployed to corporate executives.

I had never participated in a course dealing with interpersonal issues, and the events of the next five days had a profound effect on me. Neither the trainer nor the staff had an academic background in psychology, but they possessed special skills to quickly zoom in on the real causes of our problems. One man shared that he had held several jobs, but had been fired from each one after only a few months. In a short time, it became obvious to all of us—except him—that his excessive drinking interfered with his job performance. Only two days later, after one of the group exercises, he recognized the real cause. I heard later that he joined Alcoholic Anonymous (AA) and eventually became one of the leaders of that organization.

The trainer instructed us to make direct eye contact while talking with someone. He also emphasized using the pronoun “I” instead of “you” to acknowledge accountability. I was amazed to hear how often the participants switched to “you” to avoid responsibility. For example, a man who often beat his wife said, “…when you lose your temper…” instead of “…when I lose my temper…”

Lifespring frowned upon using the phrase, “I’ll try.” Instead, they recommended, “I will” or being honest and saying, “I will not.”

The question, “Do you want to be right or do you want be happy?” came up frequently. Some participants stubbornly argued for doing something just because they wanted to be right. “There are times when it is more important to be happy, even if it means sacrificing something,” emphasized the trainer. “You don’t always have to be right!”

During the lectures, we sat in wide rows. One of the presentations focused on being empathetic with others. Before the break, the trainer asked us to remove our shoes and pass them to the second person on our left. “To experience how it feels to be in someone else’s shoes, for the rest of the evening you must wear what was handed to you,” he instructed.

My feet are size nine. The loafers passed to me must have been three or four sizes larger, and I had to be careful not to lose them while walking around. Men who received women’s high-heeled shoes had much more trouble. The exercise helped me realize that I could never really understand someone until I had personally experienced what it was like to be in his or her circumstances. At the conclusion, the trainer reinforced the idea by saying, “Don't judge someone until you've walked a mile in their shoes.”

Around 10 p.m. on the second evening of the course, we were paired up and instructed to face our partners. Our assignment was to tell our partner about an incident from our lives when we had been the helpless victim of someone else’s wrongful action. When the partner was satisfied that the other person could have done nothing to avoid being victimized, we had to switch roles. When both sides were finished, the couple could sit down on the floor.

Both my partner and I told convincing stories. I was especially happy to see him agreeing about my being the victim in my upcoming divorce. We figured that was the end of the session and we could go home. We were wrong!

“Now I want you to tell the same story to your partner, except this time make yourself be accountable,” the trainer said. “Bring up everything you could have done to prevent the outcome.”

The participants burst into moans. “That’s not possible,” someone said after raising his hand.

“I’m convinced that it can be done,” the trainer replied. “We’re not leaving until everyone is done.”

To my surprise, after lengthy, sincere soul-searching, I was able to come up with possible actions that could have changed the outcome of my case. My family had already had a nice home and comfortable life in Los Altos. Nobody had forced me to compete with my father-in-law’s success. Had I been satisfied with being a design engineer, perhaps I would not be facing a divorce now.

My partner was also successful in his effort. We learned a powerful lesson that evening: when bad things are done to us by someone else, it is not always completely the other person’s fault.

At the graduation ceremony, Chuck approached me. “Les, I realize that my stubbornness has been getting in the way of my working well with the other employees,” he said. “You don’t have to worry about me anymore. I’ll fully cooperate with the group.”

Chuck kept his promise. He spent the next day at work making peace with everyone. From that day on, he became a model employee and continued to be my close friend. A month later, we both went through the Advanced Training session of Lifespring. The lessons I learned from the courses stayed with me throughout my life and helped me make better decisions along the way.

As helpful as the Lifespring courses were, they did not give me any direction in regard to saving my marriage. Having grown up without a father or a male role model, I assumed that the main task of the husband and father in the family was to provide a safe and secure environment for his family. My academic courses had only taught me how to troubleshoot technical problems and how to solve them. Without any obvious warning sign that my wife was not happy, I was unprepared to face the inevitable. No matter how much money we had, or how clever I thought I was, the frustrating truth remained—my marriage had come to an end.

Although I could not prevent the divorce, the Lifespring training eased its impact. My wife and I agreed to handle it through mediation, without hiring two adversarial attorneys. We set a goal of completing the required legal procedures by the summer of 1981.

Having grown up without a father myself, I did not want to be a typical divorced father who sees his children infrequently or never. I asked for joint 50-50 custody. Accepting that such an arrangement would not be feasible with my busy corporate role, I decided that I would resign from the company. While I was contemplating how to break the news to Comsat, Wayne announced that due to health reasons he planned to leave by the end of the year. Being second in command at CGIS, I was supposed to take over his role.

The meeting with the Comsat brass in Washington did not go well. “Several of our employees have gone through divorces, but they still function fully in their jobs,” one of the VPs told me when I gave the reason for my resignation. I explained my desire to have joint custody of my children, but he was not sympathetic. When I would not change my mind, I was threatened with a lawsuit for breaking my employment agreement.

Fortunately, in California such contracts exist mainly to protect the employee. I was able to reach an amiable compromise by agreeing to stay on part-time for another year, until our sales manager could be prepared to take over the Palo Alto facility. After Wayne’s departure, the head of the Texas division became the new CGIS president.

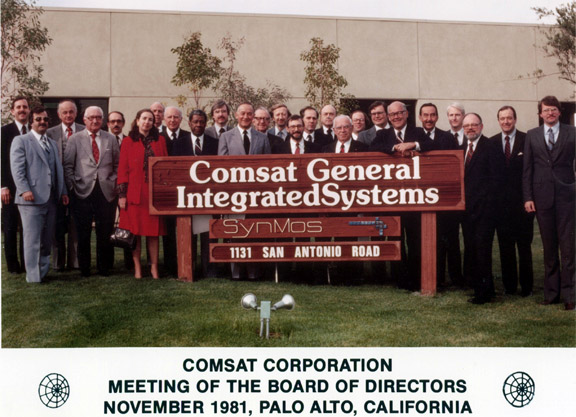

My last major official task was helping to host the Comsat directors in California at the meeting of the board. The board members came from around the country, and we made elaborate plans about what to show them. Among other things, we demonstrated our concept of an automated engineering department. For fun, prior to the demo, I asked them to guess four critical component values of a microwave amplifier which we were to design with our system.

One of the board members, a well-dressed lady, turned in the winning estimates. Even though she told me she was not an engineer, her numbers were extremely close to the actual values. I asked if she would consider working for us.

“How much would the job pay?” she asked.

“About $30,000 a year,” I replied.

She politely declined my offer. Later I learned that she was an heiress, with a net worth of more than $100 million.

|

Photo showing the Comsat officers, board members, and the CGIS officers. |

After my departure from Compact, one of our senior engineers, Bill Childs, left to join a Southern California entrepreneur, Chuck Abronson. The two of them founded a new software company under the name of EEsof. Recognizing the potentials of the newly introduced personal computer by IBM, they created and marketed a microwave circuit simulator program, Touchstone, for the PC, for $10,000―a fraction of SuperCompact’s price. Soon after, HP also entered the market with their product, Microwave Design System (MDS), written for workstations. Another small software company, Circuit Buster (later renamed as Eagleware) appeared on the scene, to sell a PC-based simulator for $500! Discouraged by the low-cost competition and loss of their key employees, Comsat decided to sell Compact’s assets to another entrepreneur, Urlich Rohde in 1985.

During the next decade the three products of the companies, Compact Software, EESOF and HP matured and developed new capabilities. A new company, Applied Wave Research also entered the market with their PC-based product, Microwave Office. Then, the acquisitions began. Ansoft bought Compact Software and renamed its programs as Ansoft designer. HP acquired Eesof and later Eagleware. When HP spun of part of its operation under the name of Agilent, the circuit simulator group went with the new group. Next, ANSYS bought Ansoft, and finally National Instruments purchased AWR. As of 2013, there is a three-way competition for circuit simulation by Agilent, ANSYS and National Intruments.