Two months after East Germans began to escape to the West through Hungary, the Cold War [*A form of political and military hostility between NATO and the Eastern Bloc countries.] showed signs of winding down. On the evening of November 9, 1989, the East German government unexpectedly opened the checkpoints of the Berlin Wall and allowed its citizens the freedom to leave. As the news spread, thousands streamed through the gates to the West.

The monstrous 12-foot-high concrete wall that for nearly 30 years had literally separated Communism from capitalism had finally been breached. Frustrated citizens on both sides attacked the hated Wall with hammers, chisels, and pickaxes. Instant celebration broke out in the Western section. Strangers hugged and kissed each other to celebrate the event. Within a year, the two Germanys would unite into a single democratic country. Due to the sudden political changes, however, my hope interview with Premier Gorbachev did not materialize. The Soviet Consulate informed me that he was too busy to talk to reporters.

The collapse of the Wall also initiated the collapse of Communism in Europe. Under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin, the Soviet Union soon dissolved. Eastern Bloc countries denounced their Communist leadership and elected new governments. The Cold War officially ended in 1991 without a battle.

I welcomed the change and wanted to grab the opportunity to establish some form of business in Hungary. Combining Western capital and Hungarian labor seemed like a promising opportunity. Two U.S. corporations, Litton Industries and Digital Microwave Corporation, showed interest in setting up a joint-venture operation in Budapest. I arranged exploratory visits for them with TÁKI and two other companies.

The task turned out to be far more difficult than I had envisioned. Under the socialist system, cost accounting had been quite different from that of American companies. A Litton Industries vice president and I saw an example when we visited Orion, Hungary’s largest television manufacturer. During our tour of the company, the Orion chief engineer proudly showed us the wave-soldering machine where the tuners of the televisions were assembled.

“What is the cost of producing one of those tuners?” asked J.R, the Litton executive standing next to me. I translated his question into Hungarian.

The Orion managers who escorted us looked puzzled. “We don't keep track of the cost,” said one of them.

“Could you produce a quick estimate?” I asked him, without translating his answer. J.R. looked at me curiously.

“Accounting will provide the answer shortly,” I said to him.

Similar questions came up during our tour, but none were answered. We also noticed several workers standing idle, smoking and chatting. “What are those men doing?” asked J.R.

“Waiting for parts to arrive.” “Waiting for maintenance to repair their equipment.” “Taking a cigarette break,” were the kinds of answers we received. J.R. shook his head disapprovingly.

Before leaving Orion, we spent time with the company’s financial group. The accountants did not have much of the information we wanted but promised to send it to us within a few days. The data never arrived. Shortly thereafter, J.R. told me that his company was not interested in a joint venture with the Hungarian companies we visited. I had a similar experience when I took a representative of Digital Microwave to Budapest.

In all fairness, our visits took place shortly after the sudden change of the political regime. The country was in complete turmoil, because the system under which they had operated for more than 40 years had completely changed. They did not have capital to operate or expand, and their Eastern European market had disappeared. Eventually, the Hungarian companies became more aligned with Western practices, and many of them either partnered with or were sold to foreign companies. I did not participate in any of those transactions.

The end of the Cold War also had a major impact on the American electronics industry. Government military spending was drastically cut, and defense companies laid off large numbers of engineers. At the same time, demand for personal communication products was on the rise. Companies producing pocket pagers and mobile telephones had problems finding experienced technical people. Engineers displaced by defense companies were not sought by companies that produced cellular phones. “Those engineers are too expensive and have been designing products for the government too long,” a personnel manager of a mobile phone company told me. “They don't fit into our operation.”

He was absolutely right. Engineers working for the defense contractors had developed high-priced, low-volume electronic systems. Performance and reliability were of the utmost importance. In contrast, the personal communication industry wanted low-cost, high-volume products. If a customer had to choose between two pagers, one with superior performance but selling for $500 and another with lower performance but selling for $50, he would choose the less expensive product. If a $50 pager failed, it would simply be replaced rather than repaired.

The universities were still teaching electrical engineering students the same courses they had offered for decades. Academia did not adapt fast enough to the changing world. Their slow response created opportunities for my training organization. We quickly developed courses to fill the needs of the new industry. In a short time, our instructors became extremely busy.

|

Left: Susan and I in our booth at a microwave conference in Boston. |

With the shrinkage of the microwave business, Cardiff made an abrupt decision to merge MSN with Defense Electronics. They offered jobs to those employees who were willing to relocate to their headquarters in Denver and terminated the rest. After three years of involvement with MSN magazine, I was quite happy to give up my role with the publication and focus on Besser Associates exclusively. My company moved to another office in Los Altos, maintaining my short commute. Three of our four college-age children no longer lived at home, and Nancy was with us only every second week. I began to travel more and more to teach courses. Susan often came with me to these workshops—I worked while she shopped. In some years, we slept more often in hotels than in our own home.

In the U.S. and Australia, the students generally addressed me by my first name. In Japan, it was always, “Besser-san.” Europeans were more formal and used “Dr. Besser.” When I informed them that I did not have a Ph.D., they gave me a surprised look and usually switched to “Professor.”

During one of my visits to Budapest, Dr. Berceli of TÁKI gave me a tour of the Technical University of Budapest and introduced me to some of the faculty members. Over and over, I had to explain to all that I was not Dr. Besser. Observing my discomfort, Dr. Berceli, who was also a full professor at the school, took me to the Dean’s office and had me wait in the lobby. “I might have good news for you,” he said, “but let me check it out first.” With that, he entered the inner office of the Dean.

He returned later with a big smile on his face. “I was right. Your accomplishments have earned you the right to receive a doctorate—not just an honorary one, but a regular degree,” he said. Seeing my surprise, he explained a long-established procedure of that university. Selected individuals, who had proven their ability but for various reasons had not completed a graduate program, could qualify for this shortcut doctorate. To become eligible, a candidate had to:

“You’ve already met the first four requirements,” he told me. “You authored COMPACT, have the two engineering degrees, taught for more than ten years at UCLA and are referred to as the ‘father of computer-aided microwave circuit design.’ Writing a thesis and defending it should not be hard for you. Then, you can truly be called Dr. Besser.”

It sounded like a good opportunity to me. I filed the required paperwork and forwarded the class notes from my microwave circuit design course. To meet the deadline set for the thesis, I focused on computer-aided design, expanding selected bits and pieces from my previous publications. It was far from being the most elegant dissertation, but I did not want to take much time away from the family and work. I hoped to overcome any shortcomings of the written material during the oral presentation.

The university gave me several choices of dates to defend the thesis. I selected one that corresponded to a scheduled European trip and went to the school to meet the examining committee. After teaching courses for nearly 20 years, I was again the student and nervously waited for the proceedings.

The committee was sympathetic and focused on practical engineering rather than pure theory. They allowed me to demonstrate an actual circuit design with the portable computer I carried with me. In the end, I was able to answer all their questions. They sent me outside the room and after a short conference asked me to return. The Dean congratulated me and informed me that I had successfully passed the examination. In 1992, at the age of 56, my formal education was complete. I had earned a Ph.D., in Hungary—and without bribing anyone!

Delighted with the outcome, I went back to my mother’s apartment with the good news. “I wish my poor parents could see how fortunate I am,” she cried happily. “They had even less schooling than I had, and now my son has a doctorate! Her joy grew as she contemplated the rosy future of her grandchildren. “Debbie will also have one soon. And George may go to medical school. I am so proud of all of you!”

I reminded her that Abraham Lincoln once said, “The important thing is not what your grandparents were, but what your grandchildren will be.”

Our worldwide travel brought many interesting experiences. My teaching took me to 28 countries on four continents, presenting courses to more than 10,000 participants. Observing the different cultures, customs and behaviors of the students in the various countries was an education for me. The quiet and formal Europeans, the respectful and polite Japanese, and the aggressive and demanding Israelis presented a sharp contrast to the laid-back, easy-going style of the American participants. After a while, I learned how to adjust my teaching style to be effective but still popular with the students of diverse cultural backgrounds.

If I asked questions during a course in the U.S., some of the better students would immediately reply—often without raising their hands. The first time I posed a question during a course in Japan, nobody responded. I soon learned the reasons for their silence. If the answer were wrong, the person might lose face. On the other hand, if the answer were correct, he could be viewed by the others as a show-off. So, it was better for them to be quiet.

Without any two-way communication, I had no feedback about the level of understanding of the class members. I couldn't tell if the pace was too fast, or if they already knew the material and were bored. Waiting through the language translation in the class made the task even more difficult. My first day of teaching in Tokyo frustrated me totally.

During dinner, I expressed my problem to an American-born sales manager who had lived in Japan for quite some time. I asked what I could do.

“Japanese people are eager to help others,” he responded. “Tell them that you’d be honored if they would assist you in setting the right pace for the course.”

I followed that advice the next day, and the class became more responsive. Encouraging them to ask questions, however, required a more unique approach.

Knowing that hard liquor was expensive in Japan, on my next trip I brought a bottle of whiskey with me. On the first day of the class, after asking them to help by answering my questions, I placed the bottle on my desk. “If at least five people ask technical questions during the morning session, I’ll give this bottle to one of you,” I told them. The group broke out in laughter, then took the bait. They asked questions, and we had a great course. I was successful using that approach many times.

One course I taught at HP-Japan, however, was different. Nothing I did broke the ice. The students watched me with blank expressions. They would not answer my questions nor would they raise any, in spite of the bottle of whiskey that was sitting in front of them. I walked out of the class at the first coffee break dejected and frustrated.

“This is the worst bunch of students I’ve ever had,” I complained to a group of HP managers who were standing some distance away from the meeting hall. “They just stare at me, looking like dummies instead of real people.”

“Besser-san, Besser-san,” cried out one of the HP application engineers, running toward us from the meeting room. “Please turn off wireless microphone!”

It was a terrible mistake, but the damage was done. My only hope was that the students were so busy talking with each other that they missed the statements I had broadcasted through the PA system. Many of the students understood enough English to catch the meaning of my words. If they did, however, there was no change in their blank expressions. I was relieved when the course was finished and I could leave. I had learned a particularly important lesson that time—the first thing to do when I stopped lecturing was to turn off the microphone immediately!

I was headed to Cambridge University in the U.K. for a CEI-organized course. During the one-hour bus ride from Heathrow to the college, I sat next to a well-dressed Englishman who was reading the sports section of a newspaper. We began to chat. After hearing my accent, he wanted to know my national origin. Once he heard that I was born in Hungary, our discussion shifted to sports. He knew what a great national soccer team my country had in the 1950s.

“Some of the Western sports, like baseball, have never captured my interest,” I confessed. “And I really don’t see what’s exciting at all about cricket,” I said while pointing to a photo in his newspaper.

“Yes, it is a strange game,” he admitted, “although I enjoy watching it.

Our discussion drifted to other subjects. “Come and see me if you have some free time,” he said when we reached Cambridge. “I would like to introduce you to my work.”

I promised I would do that, assuming he was a professor or a researcher. When we exchanged business cards, I was shocked to read his title: Head Coach of the Cambridge cricket team!

|

| My picture taken with the Cambridge cricket team. |

One afternoon after my session ended, I walked over to the cricket field. The coach introduced me to the team as “someone who knows nothing about their game.” Out of courtesy, I watched their practice. If I watched a hundred games, I still don’t think I would ever become a fan.

Normally, the instructors headed home Friday after the short courses ended. On this trip, however, Irving Kalet and I stayed for another night. Both of us had Saturday flights to the U.S., and we planned to take the bus to Heathrow early the next morning. Two attractive young CEI course facilitators, Karen and Anneli, also stayed over to finish their administrative functions with Churchill College. In the evening, they took us out for dinner to one of the popular Cambridge pubs. Our contractual arrangement specified that CEI paid all our expenses.

Irving and I were in our 60s, nearly two generations older than the predominantly male college crowd drinking and eating there. As we entered the pub with the two tall Swedish women, eyebrows immediately raised. “Dinner with Grandpa?” one of the young bucks asked sarcastically as the hostess led us to a table.

“They aren’t our grandfathers,” snapped Anneli. “Mind your own business!”

Her statement generated immediate discussions. During dinner I could feel many stares; people were likely wondering what two old geezers were doing with the young ladies. Then something—probably unprecedented—took place.

At the end of our meal, the waiter started to hand the check to Irving, who looked a few years older than I. “I’ll take that,” said Karen, as she quickly grabbed the bill.

Her action stunned the crowd for a few seconds. Up to that point, perhaps they had assumed that two well-to-do old gentlemen were taking their mistresses out to dinner, but seeing the girls paying for it was too much. Many of the students shook our hands as we were leaving, congratulating us. Irving and I just smiled and accepted their admiration. There seemed to be no reason to bother telling the students about our true connection with the girls.

When I taught courses in large cities or universities, I usually relied on public transportation. In the rural areas, if the course location and hotel were far apart, rental cars were more convenient. When Susan traveled with me, she usually dropped me off in the morning to teach and picked me up in the late afternoon. She always found ways to fill her days—visiting museums, churches, and of course, shopping, one of her favorite activities.

When Motorola asked me to teach a five-day course at Basingstoke, in the U.K., I combined it with a two-day course at a London-based conference center. That time, I traveled without my better half.

At Heathrow Airport, I picked up a rental car and took one of the motorways toward Basingstoke. Driving for the first time on the left side of the road, I quickly realized my mistake in not picking a car with automatic transmission. Shifting gears with my left hand while watching the traffic was nerve-racking. The car had no air conditioning. The effects of the heat and stress had me soaked with perspiration by the time I arrived at the hotel.

The Motorola training center was only a few blocks away from where I stayed, so I had no problem navigating there the morning. When I returned to the hotel after my first day of teaching, I learned that they did not have an exercise room. Instead of going out to run in the hot and humid weather, I inquired about local health club facilities. The front desk was very helpful and gave me directions to a gym located “about 15 minutes drive” from the hotel.

I quickly changed, jumped into my car, and headed for the gym. Unfortunately, the route included five roundabouts—most of them with more than four exits. GPS was not available in those days. Instead of 15 minutes, it took me nearly an hour and a half to reach my destination. The same thing happened on my way back. I found myself lost several times. I told myself that the next day it would be easier.

My 30 years of driving experience did not help me at all. No matter how hard I concentrated during my daily visits to that gym, I was unable to go there and return to the hotel without taking at least one wrong exit out of one of the roundabouts. I had several close calls when I slowed down momentarily to think. At the end of the week, I thanked St. Anthony for protecting me, returned the car to the airport location, and promised myself never to drive again in the U.K.—or any other country where they drive on “the wrong side of the road.” I took the bus to London for the next course.

After the first day of teaching in London, on my way back to the hotel I noticed a small crowd gathered outside the entrance of one of the Underground stations. Curiously, I joined the group and saw a man playing a shell game. Just as I joined them, I saw the player place a small ball under one of three cups. He shuffled the cups around rapidly, using both hands. Then he asked onlookers to guess which cup covered the ball. If the guess was correct, the gambler would double whatever bet was placed.

A man standing at the front of the group pointed to one of the cups and put a ten-pound note on the table. The gambler pocketed the money first, then reached out for the cup indicated by the customer. As he lifted the cup, however, he made a rapid movement and shifted the ball under another cup. Although his movement was swift, I could see that he was cheating and voiced my observation. The man who placed the bet agreed with me and demanded his money. Several others in the crowd made threatening noises. The gambler caved in and paid.

“Let's try it again,” said the winner.

The gambler placed the ball under one of the cups and shuffled them again. I did my best to follow the movements of his hands with my eyes. When he stopped, the previous bettor pointed to the same cup that I would have guessed.

“Please help me to make sure that he doesn't cheat again,” said the bettor to me. “Put your hand on the cup.”

I did as he asked, and after the man placed a ten-pound bet, the gambler lifted the cup and the ball was underneath. The crowd cheered, and the gambler grudgingly paid again.

“We’re making a good team,” said the happy winner to me. “I'm going to break this guy today.”

In the next round, the man asked me again to place my hand on the cup that we both agreed upon. “Why don't you place a bet yourself?” he asked me as he was putting his money on the table.

Although gambling is not in my blood, I could not see any risk and quickly added ten pounds to the bet on the table. All that time, I kept my eyes focused on the selected cup.

The gambler lifted the cup. To my surprise, the ball was not there. He lifted a second cup to prove that we had made a mistake. I was stunned. The gambler took our money away.

“That's OK,” said my new friend. “Let's double our bets to win our money back.” The cheering crowd endorsed his suggestion. Then, it suddenly hit me: I was being taken by the group!

“No more bets for me,” I announced and prepared to leave. The others tried to convince me to stay, but I walked away. About two blocks later, I saw a policeman and approached him. I briefly outlined my experience and asked if he would come back with me to investigate.

“I'm certain that they’re gone by now,” he told me. “They always operate near the subway stations and quickly move after they take money from the suckers.” He smiled at this “sucker” and lowered his head a bit. “You know, by placing bets yourself you are equally guilty, because gambling is illegal in England. If I arrested them, I would have to do the same with you. I suggest you forget the incident and don't fall for such a scam in the future.”

I walked back to my hotel. Thinking during dinner about the teamwork of the crooks, I could not help but admire how well the operation had been set up. Whether they were all professional actors or just experienced crooks, their role-playing was perfect. They deserved my ten pounds.

Another European course, organized by CEI Europe, took Susan and me to the city of Nice, France, during the week of their annual Mardi Gras Carnival. Our hotel, the Grand Aston, was located on the parkway where the nightly festival parade ended. The front-desk clerk led us to the best corner room on the top floor. He took us out to the spacious balcony to show us where we could watch the festival directly below us that evening. We had heard much about that spectacular parade, and we looked forward to seeing it.

As the evening approached, the crowd on the street began to swell. Bleachers set up on both sides of the wide boulevards were packed with spectators. After dinner, we bought two of the crazy hats everyone wore, mingled with the crowd, and watched the magnificent floats slowly crawl by. The noise level was so high that we had to shout to each other, but it was an amazing experience to be there.

After a while, jet lag hit both of us, and we went up to our room. For a while, we watched the procession from the balcony. Knowing that I would have to start teaching the following morning, we decided to retire. Around 10 p.m., we closed the balcony doors and went to bed.

Falling asleep, however, was not easy. The master of ceremonies was stationed directly below us. The sound of his voice, amplified by a powerful PA system, blasted through our windows. We tried using earplugs, but they could not muffle the racket.

I called the front desk. “Could we switch to another room in the rear of the hotel?” I asked.

“Sorry, but the hotel is fully booked. Is something wrong with your room?”

“The room is lovely, but we can’t sleep because of the street noise.”

“Monsieur, this is no time to sleep! You should be watching the parade.”

I gave up. We took sleeping pills, but even with the drugs, it took some time to sleep. Thankfully, the march ended around 1:30 a.m., so I had some rest.

The next day, we tried again to change rooms, but nothing was available. In desperation, I asked the person at the front desk if someone on the rear side would be willing to upgrade to our room. The idea worked. We gave up our fancy accommodation for a smaller room that looked at the outside walls of another building. We had no view, but we slept undisturbed for the rest of the week.

Because I had the same course scheduled at Motorola in Schaumburg, IL the following week, we flew back to Chicago on Saturday. Susan cleaned my overhead transparencies on Sunday, so I could use them again to teach. After dropping me off at Motorola University, Susan hit the malls. She had a black belt in shopping.

The first morning of the class ran smoothly. I had lunch in the cafeteria and returned to the classroom to begin the afternoon session. For some reason, however, at times I had trouble finding the right words. Next, one of the transparencies slipped out of my hand. When I squatted to pick it up, I landed on my rear end. What was going on?

Three times a day, I took various health food supplements. On Sundays, I filled my plastic container with the pills for that week and transferred each day’s portion to a small box every morning. That week in Schaumburg was no different from any other—with one exception. I realized that somehow I had added a sleeping pill to the noon portion of my vitamins.

I had trouble keeping my eyes open and explained to the class what had happened. The students were extremely sympathetic with the absent-minded professor and agreed to cancel the afternoon session. One of them drove me to our hotel, where I darkened the room and went to sleep.

Susan returned to the hotel mid-afternoon. When she entered the dark room, she was alarmed to find me sound asleep. Her first thought was that I was sick. She was glad to learn the truth later. She teased me for a long time about my mistake.

Seeing the success of the RF Expo conferences, another trade magazine asked me to participate in a symposium they planned to offer the following year. The proposed location was a newly constructed conference center in Chantilly, VA, about 20 miles away from Washington, DC. The organizers hoped to attract employees of the government research centers located in the DC area. The publication had a good reputation, and the location they suggested did not pose any competition to RF Expo, so I agreed. The one-week program I put together for the symposium involved seven of our most experienced and popular instructors. The magazine heavily promoted the event.

As the date of the conference approached, I suggested to the publisher that I visit the location to check out the facilities. He assured me that everything was in order, and there was no need for me to go there. Fully trusting him, I made arrangements for all of our instructors to arrive there on a Sunday and begin the courses the following day. Exhibitors were to set up their booths on Monday, and the symposium would open officially for general traffic on Tuesday.

As scheduled, Susan and I, along with our Director of Engineering, drove to Chantilly from the Washington Dulles airport on Sunday afternoon. Approaching the vicinity, however, we could not spot the expected large building. The service station attendant where we stopped for help informed us that he had never heard about any conference center nearby. Following our original directions meticulously, we arrived at the street address to find only a large single-story warehouse in a deserted shopping center. Other than a few pick-up trucks, there were no signs of life outside.

Entering the unlocked front door, I saw a group of workers standing around. The foreman told us that his crew had been hired to set up partitioned sections, but the movable walls had not arrived. The publisher appeared shortly and explained the reason: the truck bringing the building material had been involved in a major accident several hours away. Delivery would not take place.

I pinched myself hoping that this was all just a bad dream. No such luck. The building looked like an empty Costco instead of the fancy conference center I expected.

Although I was furious, this was no time to argue with the publisher—we needed a solution! Over 200 people would show up the next morning to take our courses. We could not turn them away without suffering devastating consequences to my company’s reputation.

With few options and very little time, the best we could do was to purchase metal water pipes and set up frames for classrooms. Long curtains were hung along the pipes to provide walls. Fortunately, the publisher had already ordered video projectors and screens. Using them, we were able to set up the five classrooms we would need for the courses.

The next day was one of the worst of my entire life. First, I had to face the shocked instructors when they saw the primitive conditions of their “classrooms.” Standing on the bare concrete floor, they stared at the 30-foot high ceiling. The curtains provided absolutely no sound insulation, so the students would hear simultaneous instructions from all of the lecturers. To make it worse, very early into the first session, the workers began to set up the booths of the exhibitors. The sounds of forklifts loading and unloading material, workers hammering, and people yelling instructions added to the already chaotic atmosphere. By the time the first coffee break rolled around, several of the students had had enough. They asked for refunds and left. Luckily, the majority toughed it out. It was a miracle that we survived that week.

The publishing group lost a significant amount of money on their flubbed effort to establish a new symposium. Adding insult to injury, they refused to pay us the amount agreed upon for our courses, even though they had collected the course fees during registration and the courses had been presented. Our attorney recommended a lawsuit, but after the arbitration fiasco I had gone through with the divorce, I had promised myself never to be involved with another legal battle. Rather than fighting in court, I decided to write off the miserable event as a learning experience and be more careful in the future. Even today, as Susan and I face something unpleasant, we say, “Things could be worse. Remember Chantilly!”

In 1992, I visited Taiwan by myself to teach a course at the company of my former colleague, Chi Hsieh, “The Giant”. During my first tour of his company, I noticed how sparkling clean their restrooms were. Generally, with the exception of the large Western hotels, public restrooms in Taiwan were not pleasant. When I mentioned how impressed I was to see the spotless men’s room, he shared the unique way he had established to keep them clean.

“After we moved into our new building,” he told me, “it took only a day until the restrooms became quite messy. No matter how often the janitor cleaned them, the facilities were soon again in bad shape. I called for a company meeting to discuss the problem.”

“I gave my employees two choices,” Chi told me. “Either they could manage to keep the restrooms clean themselves, or I'd do it myself.”Chi shrugged his shoulders. “But I told them if I were the one to do it, I’d be in the restroom instead of selling our products and they’d be out of work.” He smiled at me. I left it up to them to decide.”

The facilities have remained clean ever since.

Approximately 30 of the company’s engineers attended my course in their large conference room. They were far more outgoing than the Japanese students and most likely would have asked questions even if I had not offered them the bottle of whiskey at the opening. Lunch was catered in the classroom in neat wooden boxes. They ate quickly, folded their arms on the tables, laid their heads down, and went to sleep. I was the only one awake!

I took a picture of the napping group for my company’s monthly newsletter. We published the photo later with the caption “Enthusiastic students after a Besser course.” It generated lots of follow-up comments from the readers.

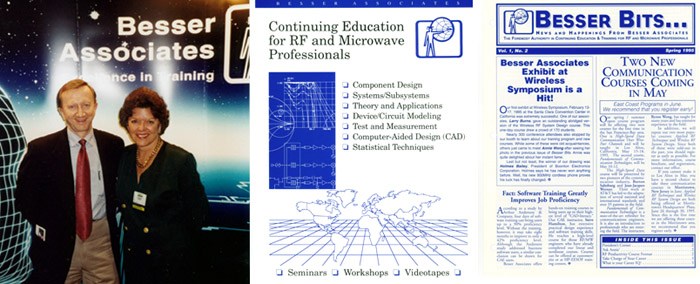

One evening Chi told me to prepare myself for something unusual. He took me to a section of Taipei called Snake Alley, which had hundreds of small shacks. In front of each establishment, vendors pointed to large cages covered with fine wire mesh and tried to lure the passersby to purchase something. Inside each cage, I saw a large number of snakes wriggling around. “Those are deadly reptiles,” said Chi. “Their venom would kill a human within minutes.”

I could not imagine why anyone would want to buy one of them, but in a few minutes I witnessed an elderly man nodding his head to the seller. Money exchanged hands. A handler, wearing a long, thick protective glove on one arm, came out from the shack and opened the top of the cage. The customer pointed to a particular snake, and the handler pulled it out by its tail. People crowded around to watch the action.

The handler picked up a razor-sharp knife with his other hand and swiftly slit open the underbelly of the helpless reptile. The vendor was already holding a glass container underneath to collect the blood. In a few seconds the snake was still, and the bright red blood flow stopped.

Next, the vendor handed the glass to the customer, who swiftly drank it. The crowd cheered and the elderly man bowed to them with a big grin on his face.

“Poisonous snake’s blood is an expensive aphrodisiac,” Chi told me. He estimated the price was at least US$100. “That old man bought some expensive fun for tonight.” I hoped Chi was right.

The snake’s blood was not the only item marketed. The handler also removed the gall bladder and the still-beating heart of the snake, tossed them into shot glasses filled with alcoholic drinks, and sold them to the highest bidders, who drank them without hesitation. According to Chi, those body parts had medicinal powers. I was both horrified and puzzled by what I had witnessed that evening.

After our experience in Snake Alley, Chi took me to buy presents. Among the stores we visited was a high-class jeweler that sold fake versions of expensive designer watches. One could buy cheap imitations of Rolexes, Guccis, Rados and other name brands on the streets, but this store offered products that looked particularly authentic. I bought a dozen different makes for all of my family members and visualized how they would impress their friends with their “high-end” timepieces.

When the course was finished, I planned to spend a week in Hawaii with George and Nancy during their winter school break. Our flights were scheduled so that the three of us would arrive in Honolulu at about the same time. Susan had planned to take Daphne and Kent to Club Med in Mexico that week.

Because I had spent almost all my travel money buying presents, I called home and asked Susan to send some cash with the children. At the Taipei airport, I purchased a few last-minute souvenirs and boarded my flight penniless.

Going through U.S. Customs in Honolulu, I declared around $700 and was prepared to use my AMEX credit card to pay the duty over the allowed limit. “What are you bringing with you?” asked the customs officer after perusing my declaration form.

“Toys, jewelry and fake watches,” I replied.

“Go to line number two for inspection,” he ordered me.

The second inspector immediately wanted to see the watches. Not remembering which suitcase held them, I rummaged through both bags. I wished that Susan had come with me—she always knew where everything was.

Finally, I found the watches and handed them to the inspector. He examined them carefully for some time. “These watches are not fake,” he said. “They are made with real gold.”

My God. The store made a mistake. Now I am in real trouble. “I thought they were only gold plated,” I mumbled.

The inspector waved to another officer to come. The two of them began to search my suitcases. Soon a third one joined in and opened the folder that had the paperwork for the course I taught.

“I see this invoice for $15,000. What was that for?” the third man asked me.

“I presented a short course in Taiwan.”

“How much cash do you have with you?”

“I don’t have any.”

“Where is the $15,000?”

“The company will wire it to our bank.”

“Are you sure you don’t have it in your pocket?”

“Of course I’m sure.”

The officers escorted me into a small room to search me. I did not realize that my children, who had arrived shortly before me, were waiting just outside the Customs area. Through the sliding doors, they watched me being led away by the customs officers. “Daddy is being arrested!” cried out Nancy. “What are we going to do?”

George tried his best to calm her down. They decided to wait for a while. If I did not come out soon, they would call their mother for advice.

After the customs officials were satisfied that I was not hiding any cash in my pockets or shoes, they returned me to the open inspection area. Their metal specialist told them that the watches were only gold plated after all. Although I had been unaware of the restriction, it was illegal to bring those counterfeit products into the U.S. They confiscated all the watches. Even worse, I had forgotten to declare a gift Chi sent to Susan. To the customs officers, I was not only a “smuggler,” but had grossly understated the value of what I was bringing into the U.S. Two strikes against me!

To the children’s and my relief, after I paid a $400 fine with my credit card, the inspectors let me go. We were heading toward Waikiki before I noticed the fake Rado I still wore on my wrist—they had missed one!

A few weeks later, I flew by myself to Switzerland to teach in Davos, one of the top ski centers of Europe. Classes met from 8:30 a.m. until noon, followed by a four-hour ski break. Instruction resumed at 4 p.m. until 8 p.m.

The unusual daily schedule was extremely popular with skiers. Many of the participants came to the classes wearing ski outfits. As noontime approached, they began to look at the clock frequently. The minute I said, “Let’s take a break,” most of them were gone. The ski lift was next to the hotel where I was teaching, and the skiers were on their way to the slopes in a few minutes. I often wonder how many of them really came to learn about circuit design.

I skied on Saturday after the five-day course had ended and headed home on Sunday. Davos had a convenient direct train to the Zurich airport, taking slightly more than two hours. As I had several times in the past, I boarded the train at 7 a.m., which allowed ample time for me to make my Zurich to San Francisco flight. The Swiss trains have a reputation for always being on time. People set their watches by the exact arrivals and departures.

As I was reading the course reviews of the students, our express train made an unscheduled stop. The other passengers were as surprised as I was. After we waited several minutes, a conductor passed through our car. “Please take your luggage and leave the train,” he announced in German, French and English. There was an accident on the line, and you’ll be transferred to a bus.”

“How much delay will that cause?” I asked him. “I need to catch an 11 a.m. flight.”

“I’m afraid that won’t be possible. You’ll arrive at the airport around noon.”

That was bad news. The conductor, however, was extremely helpful and asked the station to notify Swissair about our delay. “They’ll probably reroute you on different flights,” he said, trying to comfort me.

We learned later that at a railroad crossing ahead of us a military truck had accidentally struck a utility pole, knocking it across the rails. Power was down for a segment of the line. Buses would take passengers around the affected area. Another train would pick us up at the next station, about 25 km away, to complete our journey.

Several small, well-heated buses waited for us outside the station. I took a window seat in the first one and hoped the airline would succeed in sending me home without my having to stay in Zurich an extra day. Our convoy took off in a light snowfall.

The winding mountain road had no guardrails. Seeing the steep dropoff at the edge of the narrow snow-covered road—extremely close to the wheels—made me nervous. The driver kept a steady pace, seemingly unconcerned with the danger. I closed my eyes and hoped for the best.

We made it safely to the next station and transferred to the second train. By the time we reached the Zurich Airport, however, my flight had departed. Swissair gave me two alternatives: take the nonstop morning flight to San Francisco the next day or fly to New York via Geneva and catch the last cross-country connection of the day to San Francisco. I opted for the second choice. Sympathetic to my delay, they upgraded me to first class on the transatlantic portion. That part I liked. Although the airlines usually upgraded me to business class, the passengers in first class were even more pampered.

My flight arrived at JFK in New York 45 minutes before my United connection was scheduled to leave. According to federal regulations, all passengers had to clear Immigration and Customs. Seeing the line waiting at the immigration area, I approached a roving officer and told him about the Swiss railroad accident. “Would it be possible for me to bypass the line so I can catch my connection to San Francisco?” I asked.

The man sized me up with suspicious eyes. “No sir, you’ll just have to wait your turn.”

When I finally reached the Immigration window, the officer I had spoken to earlier walked to the agent behind the window and whispered into his ear. The agent took my passport and the customs declaration form and spent some time looking at his computer monitor. I looked at my watch impatiently.

“Seems like you are in a hurry,” he said.

“Yes. I only have a short time before the last flight leaves for the West Coast.”

“How many watches are you carrying this time?”

“None,” I smirked. “I learned my lesson the hard way.”

He did not smile. After making a mark on my customs form, he handed it back to me. “Proceed to Customs with your bags.”

I ran to the carousel, waited for my bags, and rushed to Customs. The officer there looked at my form, and without asking any questions, sent me to have my bags inspected. The two suitcases received a thorough scrutiny. The man even knocked on the covers, perhaps checking to see if they had double walls. Of course, I missed the San Francisco flight and had to stay in one of the airport hotels overnight.

Several years later when I became a US citizen, the U.S. Customs eased their attention on me. However, I was still recently refused acceptance into the Global Entry Program. I guess I’m still on their blacklist.

Susan came with me to Detroit when I was teaching a course for the Ford Motor Company. The National Car rental van that picked us up from the airport was packed with customers as we headed to their car lot. Because I was a member of their elite Emerald Club, I had the privilege of choosing any car from their fleet. As we entered the rental car lot, the driver called out my name and asked what kind of car I wanted.

Our three-year-old Nissan was already promised to George, and I wanted to try their newer model. “Do you have a Nissan Maxima?” I asked.

Suddenly, all conversation in the shuttle ceased. Everyone stared at me. Susan jerked the sleeve of my jacket and whispered, “We’re in Detroit!”

I realized the capital sin I had committed. “I was just kidding,” I shouted. “Take me to a midsize Ford.” People laughed and conversation resumed.

Ford brought a large number of participants from various countries to take my course. In addition to their U.S. employees, engineers came from Brazil, Germany, the U.K., and France. The first morning more than 100 people were waiting for me in a large auditorium. As always at the beginning of my courses, I asked them to briefly introduce themselves and say a few words about the type of work they did.

Because of the large audience, the introductions took longer than planned. As we approached lunchtime, I was about 15 minutes behind my regular schedule. “Would it be OK if we cut back the lunch break to 45 minutes instead of an hour to catch up?” I asked the group.

“Monsieur, one hour is already too short,” protested the French, sitting in the center of the front row. “We need two hours for lunch.”

“Well, if that’s what everyone wants, we can take the longer break,” I replied, “but then you need to stay in class until 6 p.m. Let’s take a vote!”

The majority of the class accepted the shorter lunch break and wanted to leave at 5 p.m., so we agreed to be back in 45 minutes. I asked them to be on time so they could see an important computer simulation I planned to show at the beginning.

The German students came back ten minutes early. Most of the others, except the French, were in the room on time. Staying with my established policy, I began the instruction. Approximately 30 minutes later, the French group walked in. Their seats were in the front row, so stepping through the tight space between the rows caused some interruption. During the coffee break, they talked about the outside restaurant where they had eaten instead of the Ford cafeteria.

I did not pay attention to them. The next day, we kept our scheduled one-hour lunchtime, and the French were late again. It was time for me to act!

After turning on the overhead projector, I set its lens slightly out of focus—not enough to make the text of my slide illegible, but noticeably blurry. Then, I rehearsed with the class the joke we would play on the latecomers and turned off the projector. The students liked my idea and agreed to play along.

In a while, the laggards showed up and took their seats. I turned on the projector and began to talk about the page on the glass.

“Excuse me, but the projection is out of focus,” said one of the French.

I turned around and looked at the screen. “It looks OK to me,” I replied.

“It’s fine.” “No problem.” “Don’t touch it,” my conspirators butted in.

The Frenchman who had spoken up first rubbed his eyes. The person next to him took off his glasses and began to clean them. Then they began to talk among themselves.

“Did you have wine with your lunch?” I asked. “Perhaps it was bad and affected your vision.”

“Well, yes we did, but we always drink wine with lunch,” he said, looking confused.

I could not keep a straight face any longer and began to laugh. The class also joined in and began to tease their French colleagues. There were no more problems with lateness the rest of the week.

In the late 1990s, another Asian trip took me to Penang, Malaysia, where I stayed in the beautiful Equatorial Hotel outside of the city. Not finding a gym within the building, I decided to go out for a cross-country run in the early morning before my teaching.

“You better stay on the road,” a guard warned me. “The forest is full of vipers, and you don't want to meet them.”

I took his advice and ran in the center of the road. It was a scary task, as hundreds of scooters buzzed by me from both directions. Still, I had more faith in the drivers than the poisonous snakes. Most of the drivers and the passengers did not wear helmets, nor did they have shoes on their feet. Occasionally, I saw families of three or four hanging onto each other on the small scooters. I guessed that safety laws were either non-existent or simply not observed.

|

Left: Bicycles and scooters waiting for at a traffic light in Penang. The pictures on the right were taken |

The class took place at Motorola's educational facility located near their plant. Over half of the students were women, in sharp contrast to other countries where the vast majority of the engineers were men. All employees wore colorful company uniforms and were eager to learn new computer-aided design techniques.

Lunch was served buffet style in another part of the building. Large trays held various foods, and I helped myself to a heaping portion. The manager of the cafeteria, a queen-sized lady, was impressed with my appetite. She gave me a big smile when I passed by her with my tray. As I began to eat, however, I found the food to be extremely spicy—far beyond my tolerance level. I could only consume part of what I had on my plate and tried to be inconspicuous when I had to dump the rest.

The following morning I ate a huge breakfast in the hotel and tucked some fruit into my briefcase. At lunchtime. I told the students that I'd stay in the classroom to work on new examples. Just as I was ready to start on the fruit, the cafeteria manager showed up in the room with a tray of food. “I heard that you're busy,” she smiled, “so I brought you lunch. Please eat.”

There was no way out. I ate most of the spicy meal, drinking lots of water to ease the burning of my digestive system. Not wanting to repeat the process, I confessed to her at the end of the day that the hot spices were more than I could tolerate. “Why didn’t you tell me on the first day?” she asked. “We often prepare special lunches for foreign visitors.”

For the rest of the week, she served me great meals. If I had found the courage to “fess up” the first day, I could have saved myself much pain.

I learned that electric power losses were standard operating procedures in that country. Twice during my one-week stay, we received notice in the classroom about brownouts. When the power was cut, the temperature in the room quickly became uncomfortably high. We moved outside and continued the lecture under a large shady tree, holding the class notes in our hands. Nobody complained. I learned to respect the easygoing, peaceful nature of Malaysians.

The hotel concierge mentioned that the nearby Snake Temple would be an interesting place to visit. One evening I discovered he was right. Behind protective screens on both sides of the walkways, various kinds and sizes of snakes were sliding in the grass or coiling on the tree branches. Monks wearing yellow robes watched the visitors to prevent possible accidental interactions. Although there was a belief that the snakes would never strike good people, the monks wanted to make sure there were no problems. As I was leaving, a group of Japanese tourists surrounded two vendors; one vendor held several vipers in his hands and the other one had a large camera. They offered to take pictures of those who would allow the snakes to crawl over them. The group tried to coerce one of their members to pose for the picture, but he was reluctant to do it.

“Go ahead,” I said to the man jokingly. “They don’t bite good people.”

“I’m not good!” he replied. “Why don’t you do it?”

Suddenly the group switched their target. “Do it, do it,” they yelled at me. “Don’t be scared!”

For some foolish reason, I agreed. The salesman placed three of his snakes on my shoulders while the Japanese tourists feverishly snapped pictures of the action. I stood motionless, feeling the cold bodies of the vipers on me and hoping that their fangs had been removed. The episode probably took less than a minute, but it seemed like a long, long time before they removed the snakes. The Japanese cheered and bowed. My heart continued to pound long after we parted.

|

Upper left: Entry to the Snake Temple. Lower left: One of the thousands of deadly residents. |

After turning down our numerous previous invitations, my half-sister and her husband decided to visit the U.S. in 1994. I arranged their travel to meet Susan and me first in Florida and then come back with us to California. We had a two-bedroom timeshare condo in Orlando, and that's where our trip began. Kati had been outside of the former Eastern Bloc countries, but her husband had not.

The four of us met at the Orlando airport, where I picked up a rental car and drove to our condo near Disney World. Both of them, particularly Lajos, were overwhelmed by the heavy traffic on the Florida freeways. Lajos was impressed by the “courteous Florida drivers.” Susan and I snickered at the compliment, remembering some of our bad road experiences in that state.

Our visitors were extremely tired after their long trip, so the following day we relaxed at the resort. During the rest of the week, we alternated between visiting the theme parks and recovering from all the walking. Our timeshare at Orange Lake Resort offered several swimming pools, hot tubs and other amenities for relaxing.

Kati was multilingual, so Susan could communicate with her easily. Lajos, on the other hand, spoke only Hungarian and Russian. Kati and I acted as translators for him. When Lajos and Susan were alone, however, they somehow managed to understand each other pretty well through gestures and facial expressions. Enjoying a vacation is a universal experience, I guess. Sometimes Kati and Lajos ventured out by themselves to explore. They enjoyed their visit immensely.

One evening at dinner, Lajos told us that so far he had a good impression of the United States. People seemed to be patient, happy and polite. He was also impressed by how well the staff at the theme parks maintained order and had the crowds wait for their turns at the various rides.

They both felt that Americans dressed too sloppily. “I can understand people wearing informal clothing while visiting Disney, but they should dress properly when going to a restaurant,” Kati said, pointing to her husband, who wore a suit and tie, as an example.

They also observed the large portions of food served in the restaurants. “I now understand why so many people are heavy in this country,” Lajos told me. He was disturbed by the amount of food thrown away at the end of most meals. “Americans are lucky to have such an abundance of food,” he added.

After a week in Orlando, we drove to Fort Lauderdale, where I was to teach for Motorola. During the ride, Lajos commented that he had liked almost everything he had seen so far. However, he did not think that such a tourist area had given him a true picture of America. “Most of the people we saw there were probably well-to-do. I want to see where the poor people live,” he said. I promised to take him to the poor areas later.

We stayed near the ocean in Fort Lauderdale. While I was teaching, Susan took our visitors to the various outlet stores and the famous Festival Flea Market. Kati and Lajos were astonished at the selection of goods and the low prices. They talked about that shopping experience for years.

Fulfilling my promise, I drove the two of them to the low-rent district of the city where the houses and the front yards were noticeably different from other neighborhoods. “This is where the poor people live,” I told Lajos.

“I see, but to whom do all those cars belong?” he asked, pointing to the big American cars parked all along the street.

“The poor people,” I replied. Actually, my answer was somewhat misleading, because most likely the finance companies owned a large percentage of each automobile. However, I did not explain that part, leaving him completely baffled by the fact that even the poor people had cars. He shook his head in disbelief.

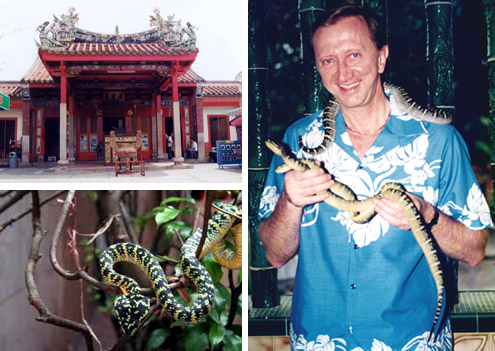

From Florida, we flew back to California. Kati and Lajos stayed with us for another week before returning to Budapest. Two local newspapers, the Los Altos Town Crier and the San Jose Mercury News, interviewed our visitors and wrote long articles about their impressions of the U.S. The Town Crier actually had a front-page picture showing Kati, Lajos and me sitting in our living room, looking at a 1956 issue of Life magazine that described the Hungarian Revolution. One of the photos in the magazine was taken during the battle for the district Communist Party building. Lajos, an Army colonel at that time, had been sent there by the Defense Ministry a day earlier to organize the defense of the building. He was seriously wounded when the building was taken by the revolutionaries. His body still carries some of the scars of injuries he suffered there.

|

Left: The three of us looking at the 1956 Life magazine story. |

At the end of their visit, they left with a vastly improved opinion of America. I was glad they had come, because they had seen with their own eyes that this country was not as the Communists described it. Yes, the U.S. had its problems, but they could now see that it might well be one of the best places in the world to live. They could finally understand why so many people wanted to come here.

A powerful new Dell laptop I had purchased arrived at our office the day before Thanksgiving in 1995. I left the machine on my desk at the end of the day after loading half of the various proprietary circuit design programs used in my courses. I looked forward to using the ultra-fast computer during my teaching and intended to complete the installations on the following Monday.

When I returned to work after the holiday, the machine was not on my desk. I asked around the office, but nobody knew about it. In addition, our sales manager’s portable radio and a couple of other items were also missing. The door lock did not show any damage or sign of tampering. I called the Los Altos police.

Detective Laranjo responded to my call and took a report of the apparent burglary. A few days later, he informed me that although he suspected an inside job by the building cleaning crew, he had had no luck finding anything. I reported the stolen items to our insurance company. Within a short time, we received full reimbursement for the lost items, and I replaced the $2,200 laptop.

The day before New Year's Eve, I received a strange phone call. “Are you missing a portable computer?” asked a man at the other end of the line.

“Yes, I am,” I replied with surprise. “Have you found it?”

“I saw two men in my company’s lunchroom trying to use a laptop. They asked me to help. Your name and your company’s name came up on the screen during the boot-up,” the man told me. “I had the feeling that the computer didn’t belong to them. Because they did not know how to use it, they offered to sell it to me for $500.”

“Hold on for a minute while I go to my office,” I said, and on another line I immediately called the Los Altos Police Department.

“Keep talking to him and see if he will bring the computer to your office,” suggested Detective Laranjo, who took my call. “I’ll wait to hear what he says.”

I switched back to the other line and told the man that I was eager to have the computer back with no questions asked. He assured me that he was not making any money on the transaction. “I just feel bad to see someone like you losing a valuable item. I’ll go back and buy it from those men,” he added, and agreed to bring the computer to our office the next morning at 10 a.m.

I relayed the information to the police. Within a short time, two detectives showed up and began to plan a sting operation. I became a key part of their scheme.

Our building had two entrances. Not knowing which one the crook would use, the police assigned plainclothes officers to watch each door and look for someone carrying a computer bag. Our receptionist would be replaced by a policewoman. They set me up with a hidden wireless microphone. Two detectives would wait in another office for my signal. I was to act natural, greet the man, and ask him to let me check the computer. Once I was convinced that the machine was mine, I was to say, “Yes, it’s mine.” At that point, two detectives would rush in to arrest him. They assured me that I would face no danger, although I was not completely convinced and trembled with excitement and anxiety.

At 9 a.m. the next morning, two detectives and the policewoman came to our office and took their positions. I rehearsed my keywords with them again. The system worked well. Then we waited for the signal from the lookouts.

Shortly after 10 a.m. the policewoman received a call from downstairs on her radio. “A possible suspect, carrying a black computer bag, is approaching the building,” I heard on the crackling message. The detectives took their hiding places, and I tried my best to look busy and calm.

Our “receptionist” knocked on the door of my office. “Your appointment is here to see you,” she announced.

I walked to the door and looked at the slightly built man next to her. He was holding a black computer bag. He smiled at me and offered his hand. I shook it and led him into the office. I offered him a chair and closed the door. “Thanks for coming here. I have the cash for you.”

“I’m so glad to help you with this,” he replied while taking the laptop out of the bag. “Please check to make sure it is the right one.”

I plugged in the computer and turned it on. As expected, my name appeared. There was no doubt it was the stolen machine. “Yes, it is mine,” I said, expecting the detectives to come through the door.

Nothing happened.

“Yes, it’s mine,” I repeated, fearing that the microphone tied to my chest was not working.

“That’s great. If you give me the money, I’ll be on my way. My girlfriend and I are flying to Las Vegas to celebrate the New Year.”

What’s wrong? Where are the detectives? What should I do? “Yes it’s mine,” I said for the third time, feeling increasingly desperate.

The man looked puzzled and began to rise from his chair. At that moment, the door burst open and the detectives rushed in. In a split second, they pushed him to the ground and handcuffed him. “Are you armed?” asked one detective.

“No, I’m not. What’s going on?”

“You’re under arrest for the suspicion of handling stolen property,” said the other detective as he began reading to the man his rights.

After they helped the man to his feet, he turned to me. “Is this what I get for being a Good Samaritan?” he asked in a convincing voice.

I did not know what to say. “Don’t pay attention to him,” the detectives told me as they led him away. They also took the computer as evidence.

Susan had been hiding in a nearby cubicle during the entire incident. When the commotion ended, she came over to me. “I was so worried about you,” she said with a sigh of relief. “I hope they lock that guy up for a long time.”

The possibility that the man had been telling the truth bothered me for some time. He did not look like a burglar and he seemed sincere. On my way home, I stopped at the police department to learn more about the case, but the detectives had taken him to a jail in San Jose. The receptionist, however, assured me that they had found enough evidence to keep him in custody.

I never found out how the thieves gained entrance to our office. The building manager stood firmly behind the cleaning crew that he had used for many years. He told me that when the cleaners come to work in the late evenings, they opened several offices and moved from one to another. It is possible that someone familiar with the cleaners’ procedure sneaked into our office while the cleaners were working in another one. After the burglary, the cleaners were ordered to keep the building as well as all the offices secured while they worked.

The next February, I received a summons to appear as a witness in the Palo Alto Courthouse. The defendant who tried to sell me my computer was also in the courtroom, but he avoided making eye contact with me during my testimony. Later I heard from the detectives that in a plea bargain for a lesser charge the man provided information about the gang that had committed several burglaries on the Peninsula.

At the 1996 IEEE MTT Conference, the editor of the Microwaves & RF magazine, Jack Browne, conducted a lengthy interview with me. He was interested about my employment with HP, the development of COMPACT, my transition from circuit design engineering to teaching, and the future directions of Computer Aided Engineering (CAE) development. I enjoyed our discussion, because it allowed me to review my 30 years of being part of the RF and microwave industry. A few months later, he published a three-page article in their CROSSTALK series.

To recognize my achievements in the RF/Microwave engineering field, the IEEE presented me with various awards. In addition to reaching their highest level of membership, a Fellow, I received the “Microwave Applications Award,” the “Career Award,” the “Third Centennial Medal,” and “Meritorious Achievement Award in Continuing Education,” and “Distinguished Educator” honors. I was also listed in Marquis' “Who’s Who in the World,” and in the “Microwave Hall of Fame.” I felt that there wasn’t anything more to achieve in my technical career and began to think about retirement. The excessive business travel was becoming extremely wearing—during some periods I was away from home more than 50 percent of the time. It was time to give up the fame and switch to a more relaxing lifestyle.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, the ongoing operation of my company concerned me more and more. I pondered two logical alternatives—either sell the company or turn it over to someone else to run. A publishing company approached me with a buyout offer but wanted to move our operation to the East Coast. I knew that none of our employees would want that. Also, my previous sellout to Comsat did not bring back good memories. I decided to pursue the second approach and began an active search for someone who could eventually take over the operation of the business. After a couple of unsuccessful trials, I found a person who had a background in both engineering and business. I transferred increasing responsibilities to him and began to phase myself out of management. Our children had already established their independent living, so Susan and I could travel selectively throughout the world to deliver our short courses.

By the year of 2000, Besser Associates was recognized as the world-wide leader of RF and wireless training. Our children had already established their independent living, so Susan and I could travel selectively throughout the world to deliver our short courses. At that point, I already presented live courses to well over 10,000 engineers, technicians and managers in our industry. Our company provided training to nearly 60,000 professionals in 29 different countries.